On May 3, 2019 the non-confidential version of the European Commission’s decision to open an in-depth investigation into Luxembourg's tax treatment of Huhtamäki was published in the State Aid Register on the European Commission's competition website. The Huhtamäki structure is a textbook example of a so-called hybrid mismatch. In my view Luxembourg's tax treatment of Huhtamäki is a textbook example of applying the general tax principles as I was taught they should be applied. Therewith it is also an example of a case that makes me wonder what the criteria are based on which Ms Vestager and her team come to the decision to investigate certain tax cases. The case again raises concerns regarding the future of one of the most important assets in the world of taxes: tax rulings.

The non-confidential version of the European Commission’s decision can be found here in English or French.

Short description of the Huhtamäki Group

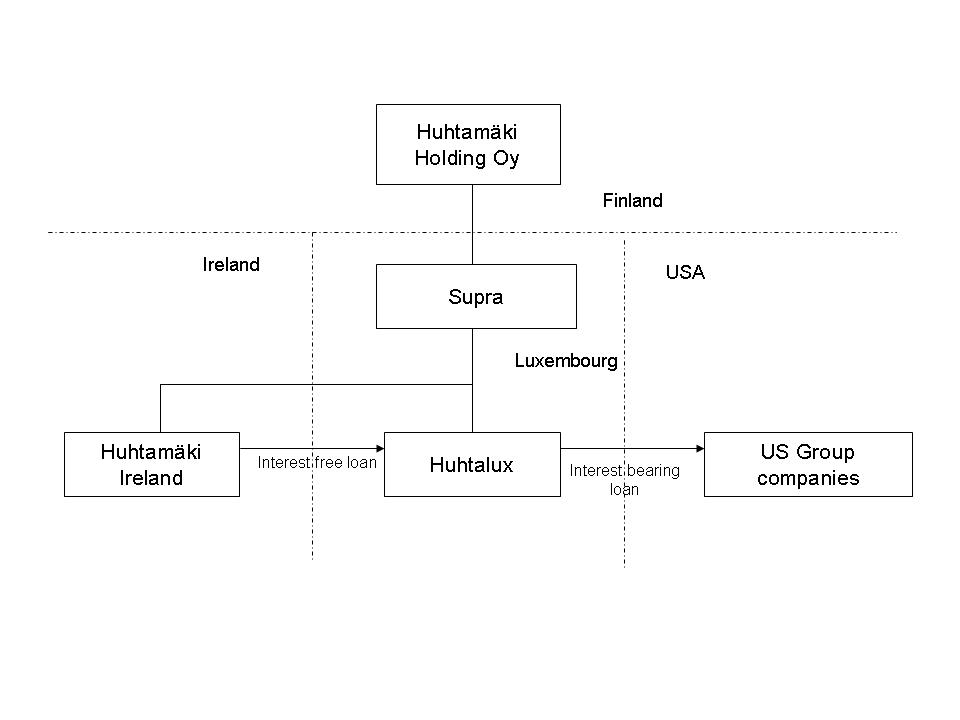

The Huhtamäki Group consists of Huhtamäki Holding Oy, a company established in Finland, and all companies directly or indirectly controlled by Huhtamäki Oy (collectively referred to as the “Huhtamäki Group”). The Huhtamäki Group has business operations in Europe, Asia, America and Oceania. According to the European Commission the Huhtamäki Group has 76 manufacturing units and 24 sales offices in 34 countries.

Supra is a company of the Huhtamäki Group based in Luxembourg. It is wholly owned by Huhtamäki Holding Oy. Supra's activity consists in the holding of participations both in Luxembourg and abroad as well as in the creation and development of such participations.

Huhtalux is another Luxembourg company of the Huhtamäki Group. Huhtalux is wholly owned by Supra. Huhtalux's activity consists in the holding of participations both in Luxembourg and abroad. In addition, Huhtalux performs group refinancing activities by means of mediumterm loans. The number of full-time equivalent employees of Huhtalux amounted to one (1) part-time employee in the period 2010-2013, four (4) full-time employees and one (1) part-time employee in 2014 and eight (8) full-time employees in the period 2015-2016.

In 2009 the Huhtamäki Group decided to restructure the then existing financing structure whereby the US group companies were financed. Until 2009 the US group companies were financed by the Swiss branch of Huhtahung KFT ("KFT"), a Hungarian resident group company fully owned by Huhtalux at the time of the 2009 tax ruling. The total amount of the funds loaned to the US group companies was approximately USD 300 million, plus accrued interest calculated at 4% or 5% plus Libor. The replacement from the previous tax structure to the current one took place in the following way:

· The receivables towards the US group companies were transferred by KFT to Huhtalux by way of capital reduction of the same amount.

· On the date it received the receivables, Huhtalux reduced its share premium by an amount equal to the amount of the receivables minus EUR 1 million against an interest-free loan granted by Supra to Huhtalux for an amount equal to the share premium reduction.

· On the same date, Supra contributed the interest-free loan to Huhtamäki Ireland in exchange for shares.

As of 2009 there was an interest-free loan outstanding with Huhtamäki Ireland as creditor and Huhtalux as debtor. The second loan was an interest-bearing loan outstanding between Huhtalux as creditor and the US companies as debtors.

A textbook example of a hybrid mismatch

In 2009 Huhtalux obtained a (first) tax ruling from the Luxembourg authorities regarding the financing structure. In this tax ruling the Luxembourg authorities confirmed that Huhtalux was allowed to make a transfer pricing adjustment with respect to the interest-free Irish-Luxembourg loan in such way that the arrangement would be at arm’s length. Consequently Huhtalux was allowed to take into account a deemed interest deduction with respect to the interest-free Irish-Luxembourg loan. Consequently the taxable income of Huhtalux was decreased with this deemed interest deduction, resulting in a spread of 3/32% remaining on this specific financing structure.

Therewith a textbook example of a classic hybrid mismatch arrangement was born. In Luxembourg a deemed interest deduction was taken into account at the level of Huhtalux. Whereas no interest income was taken into account in Ireland with respect to the same loan.

A textbook example of applying the general tax principles as I was taught

So how would I approach this financing structure?

Before answering this question I would like to point out that I was schooled in Dutch taxes and that I have a few decades of experience in both Dutch as well as international taxes. That however does not make me an expert in Luxembourg taxes. Still when one would approach me with the underlying financing structure, or any other structure, I would start with approaching the problem from the general tax principles as I have learned to know them over the years. After which I would contact an expert on the matter, in this case a Luxembourg tax expert, to discuss the structure with him or her.

Therefore I would approach the underlying financing structure as follows.

The Luxembourg-US loan

The loan that Huhtalux has granted to the US Huhtamäki group companies is interest-bearing. Therefore the only concerns I would have are:

· Is the interest rate at arm’s length?

· Is the interest deductible for US corporate tax purposes?

· Should the US companies withhold interest withholding taxes of the interest payments?

The Irish-Luxembourg loan

With respect to the Irish-Luxembourg loan I would look into the following issues:

Requalification to equity

The first matter I would be interested in is whether the risk exists that the interest-free loan should be requalified to equity. Although this is a question that is to be answered by a Luxembourg tax expert, I find it interesting to shortly discuss how I would look at this with my Dutch tax background.

Already in 1987 the Dutch Supreme Court judged in the so-called Unilever case that for how a loan qualifies for Dutch tax purposes in principle the qualification for civil law purposes is decisive. The Dutch Supreme Court however ruled that there are 3 specific situations in which the qualification for civil law purposes is set aside and in which the loan is to be requalified as equity for Dutch tax purposes:

1. In case of a sham loan;

2. In case of a participating loan; and

3. In case of a bottomless well loan.

A sham loan

This is the case when the parties actually intended to make a capital contribution instead of putting a loan in place. In such case the loan is deemed to exist only on paper and not to reflect the reality. Consequently the loan is to be requalified to equity for tax purposes.

In the facts of the Huhtamäki case as presented by the European Commission there is no indication that the Irish-Luxembourg loan is in fact a sham loan.

A participating loan

According to the Dutch Supreme Court this is the case when the loan has been granted under such conditions that the creditor has a certain participation in the debtor's business. The conditions to which the Dutch Supreme Court referred are:

· no interest is due or the interest payment is profit-dependent;

· the debt is subordinated to other creditors; and

· the term for which the loan is granted indefinite or exceeds 50 years.

According to the Dutch Supreme Court the aforementioned are characteristics that are typical of equity. The Dutch Supreme Court judged that if all three these conditions are met the loan is to be requalified to equity.

In the Huhtamäki case the first condition is met since the Irish-Luxembourg loan is interest free. I do not have enough information to decide whether also the second condition (i.e. that the Irish-Luxembourg is subordinated) is met. However, since in the Huhtamäki case the loan has a maturity date of 15 years the third condition (a maturity date of 50 years or more) is not met and therefore not all three the conditions are met. So for Dutch tax purposes the Irish-Luxembourg loan would not be considered a participating loan.

A bottomless well loan

According to the Dutch Supreme Court a bottomless well loan occurs when a loan is made between a parent company and a subsidiary, when at the moment that the loan is granted it is already crystal clear that it will never be possible for the debtor to repay the loan in full.

Again in the facts as presented by the European Commission in the Huhtamäki case there are no indications that at the moment the Irish-Luxembourg loan was put in place that it was crystal clear that Huhtalux would never be able to repay the loan in full.

Based on the above in my view based on the general Dutch tax principles the Irish-Luxembourg loan would be requalified as equity.

Possibility to take into account a deemed interest deduction

Assuming the loan would not need to be requalified to equity the next question that arises is whether Huhtalux would be allowed to take into account a deemed interest deduction with respect to the interest-free Irish-Luxembourg loan.

As most tax specialists will agree on the general principle is that related enterprises should conduct business under the same conditions as non-related enterprises would. In other words the question arises whether Huhtamäki Ireland would have granted Huhtalux an interest free loan if Huhtamäki Ireland and Huhtalux would be non-related? Again I think that most tax specialists agree that this would most likely be not the case.

And so did the Dutch Supreme Court when already in 1978 it judged in a similar case that the taxable income of the debtor should be adjusted by taking into account a deemed interest deduction (obviously in that case the debtor was a Dutch entity instead of a Luxembourg entity).

Therefore based on the general principle that related enterprises should do business under the same conditions as non-related parties would, it seems logical that Huhtalux is allowed to take a deemed interest deduction into account with respect to the interest free Irish-Luxembourg loan. And yes in a perfect (closed) system, a corresponding adjustment would be made at the level of Huhtamäki Ireland. However, since Huhtamäki Ireland is a resident of Ireland and not of Luxembourg this is not something that the Luxembourg authorities have any influence on.

Remains the question whether there are other conditions that would deny this deemed interest to be actually deducted for corporate income tax purposes (e.g. thin cap regulations, or specific anti-abuse clause, etc.). These again are topics I would discuss with a specialist in Luxembourg taxes before I would implement the Huhtamäki structure. NB in this respect it is worth noting that the Dutch corporate income tax Act for example contains an anti-abuse clause that arranges that no deemed interest can be deducted if the period for which an interest free loan is granted is 10 years or longer.

However, based on the general tax principles my preliminary conclusion would be that Huhtalux in principle would be allowed to take into account a deemed interest deduction with respect to the interest-free Irish-Luxembourg loan.

The next question that then arises is how to determine the annual amount of deemed interest that can be deducted with respect to the interest-free Irish-Luxembourg loan. In this respect it should be noted that the interest-free Irish-Luxembourg loan and the interest-bearing Luxembourg-US loan seem to be connected. Therefore it seems defendable that the taxpayer takes the position that the amount of the annual deemed interest deduction should be determined by determining an at arm’s length spread.

Other aspects

Assuming we come to the conclusion that Huhtamäki Ireland and Huhtalux are related parties that entered into a loan agreement under conditions that are not at arm’s length this means that this was done because of their shareholder relation. In my view this would lead to the following analysis.

Each year a deemed dividend distribution takes place from Huhtamäki Ireland up through the chain of its shareholders. These deemed dividend distributions are then followed by subsequent informal capital contributions down the shareholder chain, ending with an informal capital contribution into Huhtalux.

Since Huhtalux receives interest over the Luxembourg-US loan, but does not pay interest over the Irish-Luxembourg loan, Huhtalux will end up with excess cash. If Huhtalux at one point decides to distribute this excess cash to its shareholder (in this case Supra) in my view such distribution constitutes a dividend payment to Supra.

Overall conclusion

Based on the above I come to the conclusion that the Luxembourg tax treatment of the Huhtamäki Group is in line with how I would expect the treatment to be. I admit however, that one can argue whether or not the annual deemed interest deduction that Huhtalux is allowed to take into account is at arm’s length.

Tax ruling

So let’s assume I was the tax director of the Huhtamäki Group and me and my Luxembourg tax adviser came to the conclusion that based on Luxembourg law:

1. Huhtalux would be allowed to take into account a deemed interest deduction;

2. The amounts of the interest that was not paid would qualify as an informal capital contribution into Huhtalux; and

3. The distribution of the excess cash by Huhtalux would qualify as a dividend distribution.

What would I then do?

In my view I would have 2 options:

The first option is that I could trust on my analysis and implement the structure and subsequently take the positions described above in the Luxembourg tax returns that are filed on behalf of Huhtalux and Supra. However, then there would always be the risk that the Luxembourg tax authorities take another position, possibly resulting in years of fighting in courts and al that time being confronted with an uncertain tax position in the financial statements. Something that I as a tax director would like to avoid. Do what would the second option be?

The second option is that I would go for certainty and that I would contact the Luxembourg tax authorities before implementing the structure. I would then provide them with all the relevant facts together with my analysis of what the tax consequences of the structure should be. I would ask the Luxembourg authorities whether they could agree on my analysis of the tax consequences and whether they would be willing to grant us a tax ruling providing the Huhtamäki Group upfront certainty.

In 2009 I certainly would go for the option of obtaining an advance tax ruling from the Luxembourg authorities. Main reason here for is the amounts involved. Even although I might assess the risk of the structure to be low, the amounts involved are too big to have years of uncertainty.

The European Commission’s decision to start an in-depth investigation

People that follow me on social platforms might have seen that in the past I already a few times questioned Ms Vestager’s decisions to start in-depth investigations into tax ruling. Unfortunately when reading the non-confidential version of the European Commission’s decision to open an in-depth investigation into Luxembourg's tax treatment of Huhtamäki I again wonder what brings Ms Vestager to come to her decision.

The reason herefor is that when studying the Huhtamäki case my first reaction was that the Luxembourg tax treatment is a textbook example of how I think it should be. Yes, I admit not everything is perfect. As I understand Huhtamäki and the Luxembourg authorities initially seem to have agreed on a spread without a transfer pricing report being made. So perhaps the at arm’s length spread should be different. Perhaps it should not be 3/32% but let’s say 6/32%. But is that a reason to start an in-depth investigation?

The main reason for the investigation seems to be that Ms Vestager and her team are of the opinion that deviating from the remuneration that is agreed upon by related parties is only possible if this is disadvantageous for the taxpayer. In the decision it is stated that the Luxembourg law does not explicitly states that the Luxembourg authorities should also make an at arm’s length correction when this is in favor of the taxpayer. Therefore the European Commission seems to feel that making an adjustment to the remuneration in favor of the taxpayer is a discretionary power of the Luxembourg authorities, even if this is necessary to make the remuneration at arm’s length.

Whatever the outcome of the in-depth investigation will be, in my view this is a textbook example of a structure that does not deserve to be penalized with an in-depth investigation. Why? Because as stated above when reading the non-confidential version my first reaction was: This is a textbook example of how such a structure should be treated at the Luxembourg level. So I wonder why the European Commission even bothered to start an investigation into the Luxembourg tax treatment of this structure? What does trigger them to all time go after tax rulings granted by the smaller EU-jurisdictions?

The future of tax rulings

The underlying decision also makes me worry about the future of tax rulings. Why? Because in my view the Luxembourg's tax treatment of Huhtamäki seems to be straightforward. However, still this ruling attracted the attention of the European Commission. Undoubtedly Huhtamäki is not happy that its name is mentioned publicly in a case that is under scrutiny. But also the Luxembourg authorities will not be happy that again one of its tax rulings is under public scrutiny.

So what will this mean for the future of tax rulings? Tax rulings are very valuable. Both the taxpayer and the tax authorities can win a lot by coming to an upfront agreement on the tax consequences of a structure or transaction. Such a ruling avoids years of uncertainty and court cases. However, who will be happy if such rulings all the time come publicly under scrutiny of the European Commission? Furthermore the uncertainty is back. What do you gain by concluding an advance tax ruling? On top you get the bad publicity. The future will show what the European Commission’s attitude will mean for the willingness of taxpayers and tax authorities to come to an upfront agreement on the tax consequences of a certain structure of transaction.

The above are the private views of Alain J. Thielemans, which might not necessarily be the views of International Tax Plaza.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info

Stay informed: Subscribe to International Tax Plaza’s Newsletter! It’s completely FREE OF CHARGE!

and

Follow International Tax Plaza on Twitter (@IntTaxPlaza)