On January 14, 2022 on the websites of the Dutch courts an interesting judgment of the Dutch Supreme Court was published (ECLI:NL:HR:2022:17). In its judgment the Dutch Supreme Court confirms the Advocate General’s conclusion that although there might be sound business reasons for the ultimate goal of a (set of) transaction(s) still taxes may be due if the principal purpose, or one of the principal purposes, of the route that was chosen was to avoid taxes.

So why is this case so interesting? First of all because a whole generation of tax specialists in the Netherlands is raised with the adage that if sound business reasons exist for the ultimate goal, the taxpayer is allowed to choose the most tax efficient route to reach the ultimate goal. The underlying case shows that there are limits to this adage. Furthermore, the case once again shows how important it is that a good and well-organized paper trail exists that clearly substantiates what the sound business reasons are that a certain route was chosen to realize the ultimate goal.

So if you are a tax expert that was under the impression that everything goes as soon as the box: “Sound business reasons exist for the ultimate goal” has been ticked, then wake-up and smell the coffee. The underlying case shows that a second box has to be ticked. And that box is the box that reads “Sound business reasons exist for the route that has been chosen to realize the ultimate goal”.

Facts

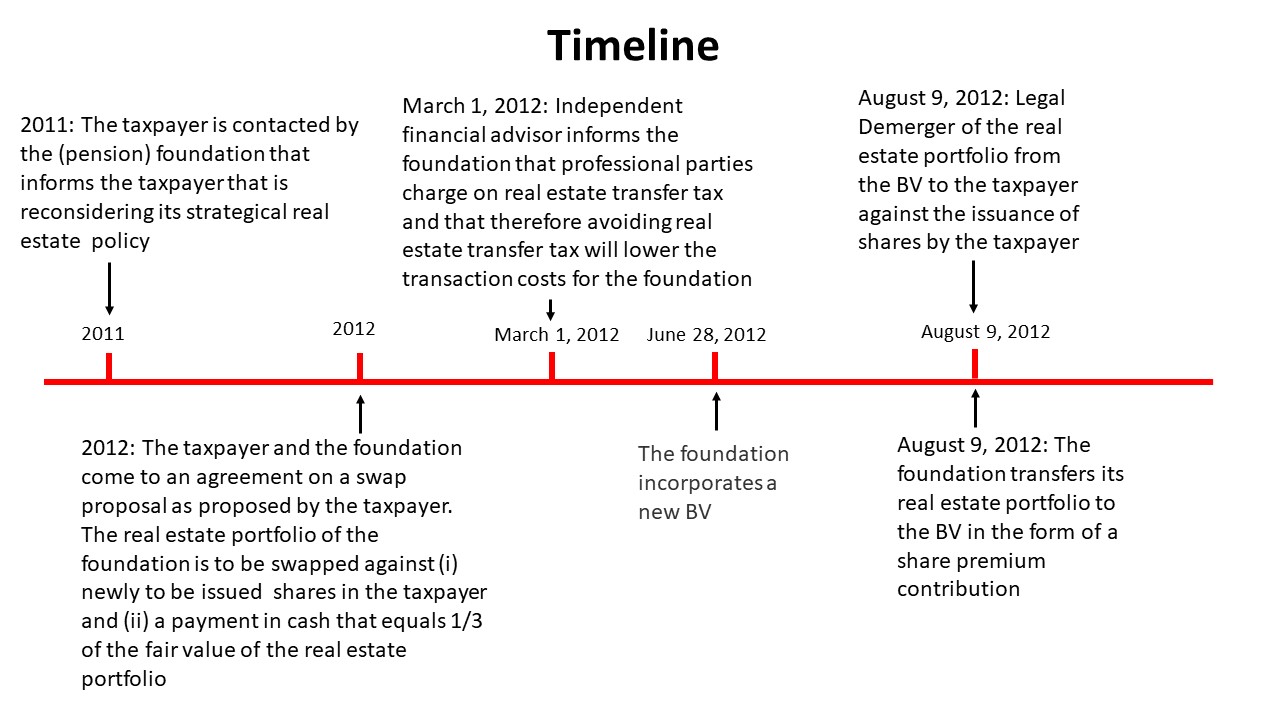

The taxpayer in the underlying case is a non-listed real estate fund. In 2011, it was approached by a so-called Stichting pensioenfonds (Hereafter: the Foundation), which reconsidered its strategic real estate policy. Part of this was the desire to convert the directly held real estate portfolio into an indirectly held real estate portfolio. This meant a real estate portfolio held via shares. The Foundation wanted to achieve this through an swap whereby its real estate would be contributed into an existing real estate fund such as the taxpayer, in exchange for shares in that real estate fund and some cash. The taxpayer was one of a few parties that the Foundation has approached to provide them with a quote/a proposal for a swap transaction.

A 2011 memo from the external financial advisor [A] to the Foundation's Asset Management Committee lists four strategy paper-based criteria for assessing swap proposals made by a real estate fund:

(i) the swap rate (the percentage of the real estate portfolio that is eligible for the exchange);

(ii) the payment mix (which part of the transaction value is paid in shares and which part is paid in cash. In this respect it should be noted that the Foundation preferred that a third of the transaction value would be paid in cash);

(iii) the nature of the counterparty; and

(iv) the size of the real estate portfolio that would remain with the Foundation.

In 2012 the taxpayer and the Foundation reached agreement in on a swap proposal as made by the taxpayer. This a agreement was laid down in an “Agreement on the main aspects regarding the transfer of real estate into and the accession to [the taxpayer]”. The agreement arranges that the Foundation will contribute the real estate portfolio to the taxpayer against (i) newly to be issued shares (of the taxpayer) and (ii) a payment in cash of approximately one third of the fair value of the real estate portfolio that is to be contributed. The Agreement also stipulates that the structuring of the transaction will partly depend on the possibilities to minimize the real estate transfer tax.

The taxpayer maintains a preference list to comply with its statutory obligation of blocking the issuance and transfer of shares. On the last day of each quarter, its shareholders can notify their entry and exit wishes, which will then be placed on that preference list. All preferences reported in this way are included in the stakeholders' quarterly report as per the last day of the quarter. Subject to the approval of the Supervisory Board, the board of directors of the taxpayer determines whether a desired share transaction can be effected. In the event of an issue or transfer of shares, existing shareholders take precedence over new entrants, except in the event of a merger or demerger, in which case the preference list does not apply.

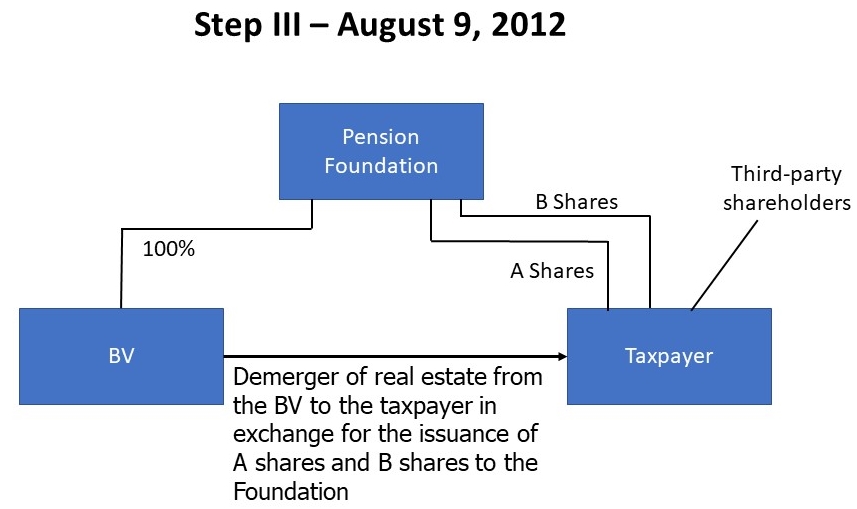

According to the bylaws of the taxpayer, it has four types of shares: A for the residential portfolio; B for the retail portfolio; C for the offices portfolio; and D for the industrial portfolio.

A memo, dated 1 March 2012, from the external financial advisor [A] to the Asset Management Committee of the Foundation states that real estate transfer tax is charged on in the price for transactions between professional parties. Consequently, avoiding real estate transfer tax reduces the transaction costs for the Foundation. The memo continues by stating that in the event of a swap transaction, real estate transfer tax can be avoided by using the exemption for legal mergers and legal demergers. However that for such exemption to apply, the Foundation's real estate portfolio must be placed in a separate legal entity. Reason here for is that the Foundation itself cannot transfer it’s real estate directly to a BV (limited partnership) by a legal demerger, since based on Article 2:334b Dutch Civil Code both entities must have the same legal form for a legal demerger.

On June 13, 2012, the taxpayer’s financial director gave a presentation regarding the progress of the transaction with the Foundation to the taxpayer’s participants' council. At that time the outcome of the discussions with the tax authorities regarding a possible exemption from real estate transfer tax was not yet known. The financial director however did mention that most likely the Foundation would opt for a full swap (exchange) instead of 2/3 against the issuance of shares and 1/3 against cash.

A memo from (the external financial advisor) [A] to the Foundation dated 3 July 2012 points out that, upon completion of the swap, as September 30, 2012 the Foundation can sell part of the shares it obtained in the taxpayer to other shareholders (of the taxpayer) and therewith still receive 1/3 of the fair value of the transferred real estate in cash.

A draft minutes of a meeting of the Asset Management Committee of the Foundation, which held on August 21, 2012, shows that the tax Inspector is of the opinion that real estate transfer tax is due over the intended transaction. It is decided to continue anyway.

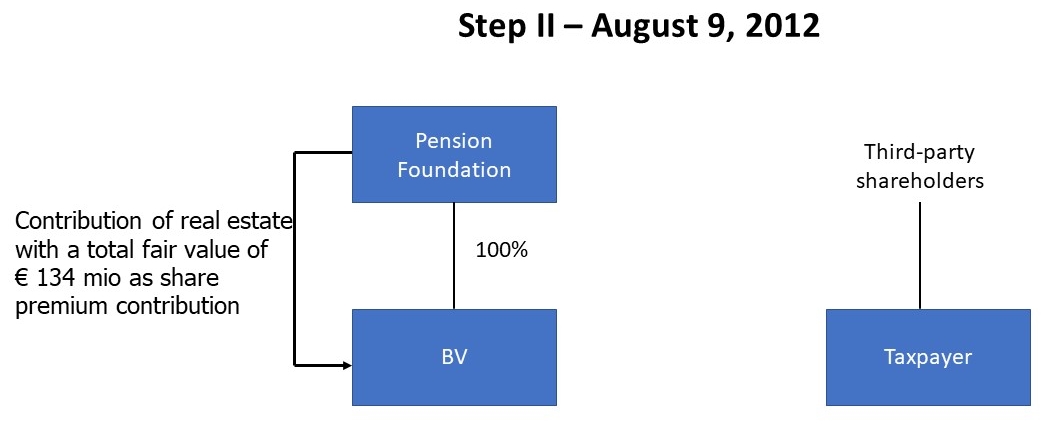

On June 28, 2012 the Foundation incorporated a BV (Hereafter: BV) in order to implement the agreement. The Foundation is the sole shareholder in the BV. On August 9, 2012 the Foundation contributed real estate with a fair value of € 134,188,000 (of which € 29,275,000 related to shops and € 104,913,000 related to residential properties) as a (share premium) contribution on shares in BV. On the same date, BV legally demerged the real estate to the taxpayer against the issuance of 111,027,061 shares with a nominal value of € 0.50 to the Foundation (A shares for the residential complexes and B shares for the shopping complexes).

With regard to its acquiring of the real estate, the taxpayer has paid €3,854,760 in real estate transfer tax when filing the real estate transfer tax return. It also lodged an objection against this payment. The Inspector rejected that objection. Parties are disputing whether or not based on Article 15, Paragraph 1, sub h of the Wet op belastingen van rechtsverkeer (Taxation of Legal Transactions Act) in conjunction with Article. 5c, Paragraph 1 of the Uitvoeringsbesluit belastingen van rechtsverkeer 1971 (Implementing Decree taxation of Legal Transactions Act (Hereafter: the Implementing Decree)) the taxpayer is entitled to the merger exemption with respect to the acquiring of the real estate.

Legal context

Article 15, Paragraph 1, sub h of the Taxation of Legal Transactions Act

Article 15, Paragraph 1 first sentence and sub h of the Taxation of Legal Transactions Act read as follows:

“1. Under conditions to be set by general decree, the acquisition is exempt from tax:

…

h. In the event of a merger, demerger, internal reorganization and transfer of tasks between associations as referred to in Article 6.33, sub c, of the Dutch Individual Income Tax Act or public benefit institutions;”

Article. 5c, Paragraph 1 of the Implementing Decree Taxation of Legal Transactions Act

Article. 5c, Paragraph 1 of the Implementing Decree:

“In case of a demerger the exemption referred to in Article 15, Paragraph 1, sub h of the Act applies when there is a transfer of assets by way of a universal succession in the context of a demerger of a company with capital divided into shares, except in the case that the demerger is mainly aimed at avoiding or deferring taxation. Unless proven otherwise, the demerger will be deemed to be primarily aimed at avoiding or deferring taxation if the demerger does not take place on the basis of sound business considerations such as restructuring or a rationalizing of the active activities of the demerging and acquiring legal entities. If within three years after the demerger, shares in the demerged legal entity, or in an acquiring legal entity, are wholly or partly, directly or indirectly, alienated to an entity that is not affiliated with the demerged legal entity and with the acquiring legal entities as referred to in Article 10a of the 1969 Dutch Corporate Income Tax Act, sound business considerations are not considered to be present, unless the contrary is demonstrated.”

Pleas of the taxpayer

The taxpayer has brought forward the following 3 pleas:

(i) the Court of Appeal wrongly considered it plausible that, although the ultimate goal of the transaction is based on sound business practices, the route via a demerger from a BV was solely motivated by tax reasons;

(ii) the Court of Appeal wrongly identified the avoidance of real estate transfer tax as the principal objective, since the finding that a demerger has as its principal purpose the avoidance of real estate transfer tax does not imply that avoiding of real estate transfer tax in this way is also contrary to the aim and purport of the EU Merger Directive;

(iii) the taxpayer sees a failure to state reasons in the opinion that the chosen route is only chosen for tax purposes and not (partly) to avoid the pre-emptive rights of the existing shareholders.

The judgment of the Dutch Supreme Court is very short and in accordance with the conclusion of the Advocate General that was delivered on November 3, 2021 (ECLI:NL:PHR:2021:1037). In its judgment the Supreme Court specifically refers to the considerations 6.2 through 6.11 of the conclusion of the Advocate General.

From the conclusion of the Advocate General

6.1 The taxpayer pleas that the (un)businesslike nature of the legal route of the real estate cannot be assessed separately from the businesslike nature of the ultimate goal of the operation. In its view, the manner in which the real estate has been demerged must be seen in the light of the ultimate goal as only one of the circumstances that may indicate a lack of sound business reasons.

6.2 I believe that this argument essentially implies that if the ultimate goal of the operation is undisputedly based on sound business reasons, the route towards it must in principle always be regarded as based on sound business reasons, or at least that the non-tax inexplicability of that route cannot lead to a refusal of a facility. In my view, however, this view finds no support in the law. It is contradicted by the so-called Kunstgrepen judgment (HR BNB 1991/317), the Mauritius (HR BNB 2015/165) and Hunkemöller (HR BNB 2021/137) judgments and the (national) Zwijnenburg judgment (HR BNB 2008/245). However businesslike the ultimate goal might be, the chosen (detour) route to get there must also be primarily motivated by sound business considerations. The parliamentary history also clearly shows that it is necessary to examine whether the “demerger or merger as a whole, and the way in which it is designed” are mainly motivated by sound business considerations.

6.3 To the extent that the pleas (i) and (ii) complain about separate testing of the (un)businesslikeness of the route to an undisputed business goal, they therefore fail in my opinion. However businesslike the goal, it does not justify means chosen merely for their anti-tax effect.

6.4 The taxpayer then rightfully (as also expressly considered by the CJEU in the Halifax case (ECLI:EU:C:2006:121)) argues that if there are more legal options available to execute a proposed business transaction, a taxpayer may choose the most favorable one. In the underlying case, in addition to the option chosen, also the following options existed: (i) the selling of the real estate by the Foundation to the taxpayer followed by a purchase of shares in the taxpayer, and (ii) exchanging the Foundation's real estate for shares in the taxpayer. Both these routes would have led to real estate transfer tax being levied over the fair value of the real estate. The question that arises is whether instead of opting for one of these forward route, opting for a route in which the Foundation incorporates a BV in order to contribute the real estate to this BV against shares and immediately thereafter demerging the real estate again for shares in the taxpayer should be regarded as an unbusinesslike detour, or 'artifice' in the meaning of the case law cited above, or as CJEU has put it in corporate income tax cases: an (entirely) artificial construction.

6.5 Given the fact that the demerger exemption for transfer tax purposes in principle must be applied in accordance with how the demerger exemption is applied for corporate income tax purposes and the latter exemption must in its turn be applied in accordance with the Directive (see HR BNB 2021/35), the main rule for the transfer tax purposes is that the demerger exemption in principle applies to a demerger as meant in the Directive and that this is only different if tax fraud or tax avoidance is the principal purpose, or one of the principal purposes of the demerger (ECJ in the Foggia case). A demerger is considered to have tax fraud or tax avoidance as (one of the) principal purpose(s) if it is not done for sound business reasons such as restructuring or rationalizing of the activities of the companies involved.

6.6 For the explanation of the Dutch implementation legislation and of Article 5c, Paragraph 1 of the Implementing Decree, in particular of the term 'business reasons' as included in that provision, therefore the CJEU’s interpretation of the misuse provision in the Merger Directive is leading. It appears from this interpretation (see the case Kofoed case, Case C-321/05) that the question of whether tax avoidance is (one of) the principal purpose(s) for a demerger must be aligned in accordance with the general anti-abuse rule as laid down in EU-law, which includes two criteria:

(i) it must be the predominant intent of the parties to obtain a tax benefit (subjective criterion; tax avoidance purpose) and

(ii) notwithstanding the formal fulfillment of the legal conditions governing the benefit , the aim as intended by the law is not achieved (objective criterion: conflict with the aim and purport of the law).

6.7 Now that it is not disputed that sound business reasons existed for the ultimate goal that parties aimed tom achieve, it only concerns the (un-)businesslikeness of the chosen route (through the contribution of the real estate into and the immediate demerger of that real estate out of a BV that was established solely for that purpose). It follows from the judgment in the Foggia case that a demerger that is based on various objectives, including tax ones, can (still) be at arm's length if the tax considerations in the context of the proposed transaction(s) are additional, or at least not decisive. The taxpayer argues the (sole) non-tax reason for the chosen route is to circumvent its preference list, which gives priority to the existing shareholders when issuing new shares, but not when transferring real estate under universal title against the issuance of shares, such as in the event of a merger or a demerger.

6.8 The Inspector has to demonstrate that the criteria for establishing one of the two presumptions of evidence mentioned above in consideration 6.6 have been met. If he succeeds in doing so, the taxpayer bears the burden of disproving that presumption by demonstrating that sound business reasons for the demerger exist. In my view, the Court of Appeal correctly allocated the burden of proof.

6.9 According to the Court of Appeal, the Inspector has made it plausible that:

(i) the Foundation kept the option open to transfer one third of the shares it would acquire in the taxpayer through the demerger to existing shareholders (with preferences) of the taxpayer;

(ii) discussed this with the interested party; and

(iii) the existing shareholders were prepared to do so.

The Court has further established that no document sets out a non-tax reason for the contribution and demerger route, while various documents emphasize that the transaction would be designed as tax-efficient as possible. It is also established that, in the absence of tax consequences, the other two routes mentioned were more obvious than the route that was chosen. I am of the opinion that the Court could base its factual judgment on the aforementioned and that the main purpose of the route chosen was the avoidance of real estate transfer tax, i.e. a non-commercial purpose within the meaning of the Directive (see the Leur-Bloem case, Case C-28/95 (ECLI:EU:C:1997:369)), with which the subjective criterion of the EU General Anti-Abuse Rule and the specific non-essential criterion as laid down in art. 15, Paragraph 1, sub a of the Merger Directive are met.

6.10 The purpose of the anti-abuse clause in the demerger exemption is on the one hand to prevent the real estate transfer tax from being an obstacle in the choice of the economically most desirable legal form of the company or the positioning of immovable property within a group, and on the other hand the abuse or improper use of the exemption by imposing a continuity requirement and preventing a sale from being presented as a contribution. In this case real estate transfer tax did not preclude the most desirable legal form, now that the transfer of the real estate into the BV was exempt under the internal reorganization exemption as laid down in Article 5b of the Implementing Decree. Nor was the positioning of the real estate within the group of the Foundation hindered by the levying of real estate transfer tax over the demerger, since this demerger did not take place 'within the group', but actually moved the real estate to a third party. Taxed is a step that can be seen as the alienation of the real estate by the Foundation to the taxpayer (in terms of the history of the Law: a 'sale that is disguised' as a demerger, albeit not against cash but against kind).

6.11 I believe that it follows from the aforementioned that an exemption of the disputed operation would conflict with the aim that the legislator had in mind with the demerger exemption as included in the Taxation of Legal Transactions Act. I would add the following: the Implementation Decree denies the exemption if “the demerger is mainly aimed at avoiding or deferring taxation.” Barring evidence to the contrary, such motives are assumed if “the demerger is not taking place for sound business reasons such as restructuring or rationalizing of the active activities of the demerged legal entity and the acquiring legal entities.” As a result of this legislative technique, the objective and subjective element more or less coincide: acquisition by demerger is exempt, unless the demerger takes place for (anti-)tax reasons. Now that the subjective criterion has been met (the choice for a full demerger that takes place immediately after the acquisition of that real estate by a BV that was specifically established for that purpose, which was mainly motivated by the wish to avoid real estate transfer tax that would be payable in the event of a business merger (direct contribution of the real estate to the taxpayer partly against newly to be issued shares and partly against cash). In the underlying case, the objective criterion is therefore more or less automatically met: the purpose and purport of the demerger exemption are to exempt demergers unless the demerger is motivated by the wish to avoid real estate transfer tax. Therewith also the objective criterion is met.

6.12 Therefore I am of the opinion that the please (i) and (ii) also fail on this point.

The full text of the judgment from the Dutch Supreme Court in the underlying case can be found here.

The full text of the conclusion of the Advocate General in the underlying case can be found here.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info

Follow International Tax Plaza on Twitter (@IntTaxPlaza)