Occasionally one stumbles over a court case that makes one wonder how it is possible that the case ended up in court. This week I had that when I stumbled over a judgement of the District Court of The Hague in a case in which the Dutch tax authorities accused a ‘multinational group’ of establishing a group structure with as main purpose to avoid taxes. In its judgment the District Court of The Hague amongst others ruled that in the underlying case a later change in regulations do not allow an avoidance motive to arise with retroactive effect.

So, what are the (simplified) facts?

Facts

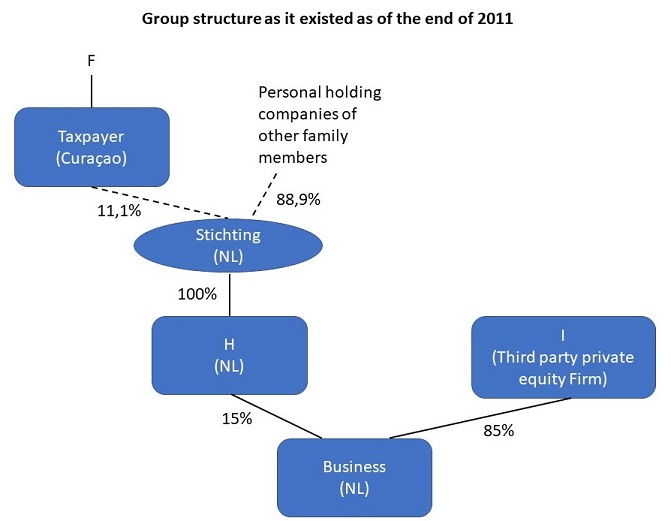

On December 28, 2007 the taxpayer in the underlying case was incorporated under Dutch law. The taxpayer is the personal holding company of F, who is also the sole shareholder of the taxpayer. At the time of incorporation of the taxpayer, F already had been living in Curaçao for quite some time. The effective management of the taxpayer is done by G, the father of F. Since 2007, together with other personal holding companies of family members of F, the taxpayer has been participating in BV 2 (the business).

On January 27, 2011 H BV (H) was incorporated to facilitate the sale of 85% of the shares in the business to the private equity company I. The shareholder of H is a so-called Stichting Administratiekantoor (the Stichting). The certificate holders of the Stichting are the personal holding companies of the family members. The taxpayer holds certificates in the Stichting that entitle the holder to an economic interest of 11.11% of the assets held by the foundation.

As per December 31, 2011 G emigrated to Curaçao. After the emigration G stayed on as the managing director of taxpayer. Consequently, as of that date the taxpayer’s actual management was moved to Curaçao and the taxpayer became a resident of Curaçao. The taxpayer’s interest in H did not change since its place of effective management was moved.

At the end of 2015 H and I sold the business to a non-related third party. In January 2016 H distributed the proceeds of the sale to the Stichting. Subsequently the Stichting has distributed the proceeds of the sale to the certificate holders. In this respect the taxpayer received an amount of EUR 13.8 million. The taxpayer did not redistribute this amount to F.

Dutch corporate income tax a high-level explanation

Under the Dutch corporate income tax Act corporations that are resident in the Netherlands are taxed over their worldwide income. Corporations that are not residents of the Netherlands are only taxed over certain income that originates from the Netherlands. One of these incomes is so-called income from aanmerkelijk belang. A so-called aanmerkelijk belang exists if a taxpayer has a direct or indirect interest of at least 5% in a company which capital is divided into shares.

With respect to income originating from aanmerkelijk belang the Dutch corporate income tax Act contains an anti-avoidance provision that contains a sort of principal purpose test. In 2016 the anti-avoidance regulation read as follows:

“The Dutch income is the total amount of:

…

b. The taxable income stemming from an aanmerkelijk belang as meant in Chapter 4 of the Dutch Individual Income Tax Act in a Dutch partnership which capital is divided into shares, not being a qualifying (tax exempt) investment company if the main purpose, or one of the main purposes, for the taxpayer having the aanmerkelijk belang is to avoid the levying of individual income tax or of dividend withholding from another party and there is an artificial construction or series of constructions where:

1° a construction can consist of several steps or parts;

2° a construction or series of constructions is considered to be artificial insofar as it has not been set up on the basis of valid business reasons that reflect economic reality;”

Obviously international arrangements like the parent-subsidiary directive, agreements for the avoidance of double taxation, etc. can limit the right of the Netherlands to levy taxes over such income.

In this case especially 2 of such ‘international’ arrangements are important. Namely the Belastingregeling voor het Koninkrijk (BRK) (Tax arrangement for the Kingdom of the Netherlands) and the Belastingregeling Nederland Curaçao (BRNC) (Tax arrangement Netherlands – Curaçao). Until December 31, 2015 the BRK applied to the underlying case and as of January 1, 2016 the BNC applied to the underlying case.

Under the BRK (so the arrangement that applied until December 31, 2015) the Netherlands would have been allowed to withhold 15% Dutch dividend withholding tax over the dividends. However under the BNC that applied to the underlying case when the distribution was actually made, the Netherlands was no longer allowed to withhold Dutch dividend withholding tax over the dividends.

The dispute

The Dutch tax authorities and the taxpayer are disputing whether or not, based on (the anti-abuse provision of) Article 17, Paragraph 3, preamble and letter b of the Dutch corporate income tax Act, the dividend distribution made from H (via the Stichting) to the taxpayer is taxable in the Netherlands

The taxpayer argues that the anti-abuse provision of Article 17, Paragraph 3, preamble and letter b of the Dutch corporate income tax Act does not apply. According to the taxpayer in the underlying case no abuse exists. To its opinion in the underlying case a customary holding structure is in place. The residency of the taxpayer was moved to Curaçao for non-tax reasons. Until the entry into force of the BRNC (as per January 1, 2016) dividend distributions to the taxpayer would be taxed with 15% Dutch dividend withholding tax. Under the BRNC the Netherlands is no longer allowed to withhold dividend withholding tax over dividend distributions made to the taxpayer. According to the taxpayer the change in regulations cannot lead to the coming into existence of a motive to avoid taxes. In the alternative, the taxpayer argues that Article 17, Paragraph 3, preamble and letter b of the Dutch corporate income tax Act only applies from the end of 2015, being the moment at which the shares in the company were sold.

The Dutch tax authorities argue that the anti-abuse provision of Article 17, Paragraph 3, preamble and letter b of the Dutch corporate income tax Act applies. According to the tax authorities the taxpayer meets the requirements for application of this provision and there is abuse. If the taxpayer would not have been in place, more Dutch tax would be owed, which satisfies the subjective condition. The tax authorities furthermore argue that the taxpayer does not run an enterprise, as a result of which the objective condition is met. The taxpayer's motive for the emigration at the end of 2011 is not considered relevant by the tax authorities. To substantiate its position, the tax authorities refer to the judgment of the Dutch Supreme Court of January 10, 2020. According to the tax authorities, there is no support to be found in the applicable laws and regulations that the alternative position of the taxpayer.

From the considerations of the Court

The Court states first and foremost that taxpayer has stated without being contradicted that it moved from the Netherlands to Curaçao at the end of 2011 for non-tax reasons. The District Court takes this as its starting point, also because there is no basis for a different conclusion to be found in the case documents.

Furthermore, it is established that after the move to Curaçao on the basis of the BRK dividend distributions from H - via the Stichting - to the taxpayer would initially be taxed with 15% Dutch dividend withholding tax. The BRK has been replaced by the BRNC. The BRNC was announced on September 30, 2015 and it came into effect on December 1, 2015 and the application of the BRNC is January 1, 2016. This means that under the BRNC, from January 2016 in principle dividend distributions to the taxpayer are no longer taxed in the Netherlands and that from that moment Curaçao has the sole right to tax these dividend distributions, unless Article 17, Paragraph 3, preamble and letter b of the Dutch corporate income tax Act applies. It has not been argued or shown that, in view of the date of publication of the BRNC, the taxpayer has deliberately postponed the sale of the business until the end of 2015 or that the dividend distribution was postponed until after January 1, 2016.

It is not in dispute that if the taxpayer would not have been in place more Dutch tax would be owed than in a structure with the taxpayer. In the opinion of the District Court, in view of what the Supreme Court has considered, according to the District Court this provides a presumption of evidence that abuse occurs. However, this does not affect, as can also be deduced from parliamentary history, that for Article 17, Paragraph 3, preamble and letter b of the Dutch corporate income tax Act, the construction must be assessed in its entirety and a taxpayer can provide evidence to the contrary in order to unnerve the existing suspicion of abuse.

To the opinion of the Court, the taxpayer has met its burden of proof. The taxpayer has made it plausible that in her case there is no evasion motive exists. The main purpose or one of the main purposes of avoiding the levy of income tax or dividend tax from another person is therefore not the reason why the taxpayer keeps its interest. When taxpayer was incorporated in 2007, a customary domestic holding structure was established. The place of residency of the taxpayer was moved to Curaçao in 2011 for non-tax reasons. Dividends to taxpayer were subject to 15% dividend withholding tax on the basis of the BRK, which applied until 2016. The District Court finds it impossible to see why the amendment of the BRK into the BRNC results in the taxpayer having or getting an evasion motive, whether or not with retroactive effect. In the underlying case there is no artificial interposing of an entity to avoid taxation. Therefore no room exists for the application of an anti-abuse provision. In view of the foregoing, Article 17, Paragraph 3, preamble and letter b of the Dutch corporate income tax Act does not apply and the assessment, and the interest decision, must be reduced to nil. The alternative argument of the taxpayer does not require further consideration.

Conclusion

Although I fully understand the focus that tax authorities have on tax avoidance, in this case I really do not understand how the Dutch tax authorities came to the conclusion that the fact that an ‘international’ tax agreement is replaced with another ‘international’ tax agreement (or tax regulations) that is (are) more beneficial for a taxpayer years after a group structure was established would lead to the conclusion that the main purpose (or one of the main purposes) for establishing the group structure was to avoid taxes. And then even going to court over the dispute that has arisen.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info