On February 16, 2023 on the website of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) the judgment of the CJEU in Case C-707/20, Gallaher Limited versus The Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, ECLI:EU:C:2023:101, was published.

This request for a preliminary ruling concerns the interpretation of Articles 49, 63 and 64 TFEU.

The request has been made in proceedings between Gallaher Limited (‘GL’), a company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom, and the Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (United Kingdom) (‘HMRC’) concerning whether GL is subject to a tax charge, without the right to defer payment of the tax, in respect of two transactions involving the disposal of assets to companies not having their residence for tax purposes in the United Kingdom, forming part of the same group of companies as GL.

The dispute in the main proceedings and the questions referred for a preliminary ruling

24 GL belongs to the Japan Tobacco Inc. group of companies (‘the JT group’).

25 The JT group is a global group which distributes tobacco products in 130 countries worldwide. The company at the head of that group is a listed company which is resident for tax purposes in Japan.

26 It is apparent from the order for reference that the company at the head of the JT group for Europe is JTIH, a company resident for tax purposes in the Netherlands (‘the Netherlands company’) and GL’s indirect parent company, the family relationship between the Netherlands company and GL being created through four other companies, all established in the United Kingdom.

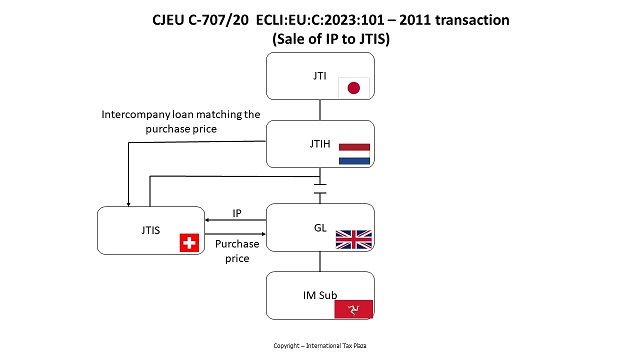

27 In 2011, GL disposed of intellectual property rights relating to tobacco brands and related assets (‘the 2011 disposal’) to a sister company, JTISA, which is resident for tax purposes in Switzerland (‘the Swiss company’) and which is a direct subsidiary of the Netherlands company. The remuneration received by GL as consideration for that disposal was paid by the Swiss company, which, for that purpose, had been granted inter-company loans by the Netherlands company for an amount corresponding to the amount of that remuneration.

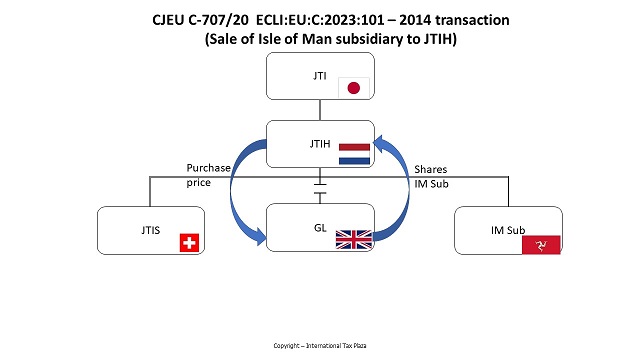

28 In 2014, GL sold all of the share capital which it held in one of its subsidiaries, a company incorporated on the Isle of Man, to the Netherlands company (‘the 2014 disposal’).

29 HMRC adopted two partial closure notices concerning the 2011 disposal and the 2014 disposal, respectively, determining the amount of the chargeable gains and profits that accrued to GL in the context of those disposals in the relevant accounting periods. As the assignees were not resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom, the gains on the assets were the subject of an immediate tax charge, no provision of national tax law providing for the deferral of that charge or for payment of the tax in instalments.

30 GL lodged two appeals against those two partial closure notices before the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber).

31 In those appeals, GL claimed, in essence, a difference in tax treatment between the disposals of assets at issue in the main proceedings and the disposals made between the members of a group of companies having their residence or their permanent establishment in the United Kingdom, which benefit from an exemption from corporation tax. It is apparent from the order for reference that the group transfer rules provide that a disposal of assets between group companies that are within the scope of United Kingdom tax must take place on a tax-neutral basis.

32 In the first place, as regards the appeal lodged against the partial closure notice concerning the 2011 disposal (‘the 2011 appeal’), GL claimed, first, that the fact that it could not defer payment of the tax charge constituted a restriction on the Netherlands company’s freedom of establishment. Second, in the alternative, it maintained that the fact that it was unable to defer that payment entailed a restriction on the right of the Netherlands company and/or GL to the free movement of capital. Third, GL argued that, although the United Kingdom was justified in taxing the accrued gains based on a balanced allocation of taxing powers between the Member States, the requirement to pay the tax immediately, without an option to defer payment, was disproportionate.

33 In the second place, as regards the appeal lodged against the partial closure notice concerning the 2014 disposal (‘the 2014 appeal’), GL claimed, first, that the fact that it could not defer payment of the tax charge constituted a restriction on the Netherlands company’s freedom of establishment. Second, it maintained that, although, in principle, the United Kingdom was justified in taxing the accrued gains based on a balanced allocation of taxing powers between the Member States, the requirement to pay the tax immediately, without an option to defer payment, was disproportionate.

34 On the ground that it had lodged the 2011 and 2014 appeals, GL deferred payment of corporation tax pending the determination of the appeal, as it was entitled to do under Section 55 of the TMA 1970.

35 The First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) concluded that there were good commercial reasons for each disposal, that neither disposal formed part of wholly artificial arrangements that did not reflect economic reality and that neither of the said disposals had the avoidance of tax as its main purpose or one of its main purposes.

36 That tribunal held that EU law had been infringed as regards the 2014 disposal, but not as regards the 2011 disposal. It thus allowed the 2014 appeal, but dismissed the 2011 appeal.

37 In that respect, as regards the 2011 appeal, it inter alia held that there was no restriction on the Netherlands company’s freedom of establishment. With regard to the right to the free movement of capital, it held that that right could not be relied upon because the legislation at issue in the main proceedings applied only to groups consisting of companies under common control.

38 In the 2014 appeal, it inter alia held that there was a restriction on the Netherlands company’s freedom of establishment, that that company was objectively comparable to a company within the scope of United Kingdom tax and that the absence of a right to defer payment of the tax was disproportionate.

39 GL appealed against the decision of the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) dismissing the 2011 appeal to the referring tribunal, the Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber, United Kingdom). HMRC, for its part, appealed against the decision allowing the 2014 appeal before the same tribunal.

40 The referring tribunal states that the question that arises in the case in the main proceedings is whether, in the context of the 2011 and 2014 disposals, the imposition of a tax charge without the right to defer payment of the tax is compatible with EU law, more specifically, in relation to both disposals, with the freedom of establishment provided for in Article 49 TFEU and, in relation to the 2011 disposal, with the free movement of capital referred to in Article 63 TFEU. The referring tribunal also raises the question of the appropriate remedy that would have to be provided if the imposition of a tax charge without the right to defer payment of the tax were considered contrary to EU law.

41 In those circumstances, the Upper Tribunal (Tax and Chancery Chamber) decided to stay the proceedings and to refer the following questions to the Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling:

‘(1) Whether Article 63 TFEU can be relied upon in relation to domestic legislation such as the group transfer rules, which applies only to groups of companies?

(2) Even if Article 63 TFEU cannot more generally be relied upon in relation to the group transfer rules, can it nonetheless be relied upon:

(a) in relation to movements of capital from a parent company resident in an EU Member State to a Swiss resident subsidiary, where the parent company has 100% shareholdings in both the Swiss resident subsidiary and the UK resident subsidiary on which the tax charge is imposed?

(b) in relation to a movement of capital by a wholly owned subsidiary resident in the [United Kingdom] to a wholly owned Swiss resident subsidiary of the same parent company resident in an EU Member State, given that the two companies are sister companies and not in a parent-subsidiary relationship?

(3) Whether legislation, such as the group transfer rules, which imposes an immediate tax charge on a transfer of assets from a UK resident company to a sister company which is resident in Switzerland (and does not carry on a trade in the United Kingdom through a permanent establishment), where both of those companies are wholly owned subsidiaries of a common parent company, which is resident in another Member State, in circumstances where such a transfer would be made on a tax-neutral basis if the sister company were also resident in the [United Kingdom] (or carried on a trade in the [United Kingdom] through a permanent establishment), constitutes a restriction on the freedom of establishment of the parent company in Article 49 TFEU or, if relevant, a restriction on the freedom to move capital in Article 63 TFEU?

(4) Assuming Article 63 TFEU can be relied upon:

(a) was the transfer of the brands and related assets by GL to [the Swiss company], for a consideration which was intended to reflect the market value of the brands, a movement of capital for the purposes of Article 63 TFEU?

(b) did the movements of capital by [the Netherlands company] to [the Swiss company], its Swiss resident subsidiary, constitute direct investments for the purposes of Article 64 TFEU?

(c) given that Article 64 TFEU only applies to certain types of capital movement, can Article 64 apply in circumstances where movements of capital can be characterised as both direct investments (which are referred to in Article 64 TFEU) and also as another type of capital movement not referred to in Article 64 TFEU?

(5) If there was a restriction then, it being common ground that the restriction was in principle justified on overriding grounds in the public interest (namely, the need to preserve the balanced allocation of taxing rights), was the restriction necessary and proportionate within the meaning of the case-law of the [Court of Justice], in particular in circumstances in which the taxpayer in question has realised proceeds for the disposal of the asset equal to the full market value of the asset?

(6) If there was a breach of the freedom of establishment and/or of the right to free movement of capital:

(a) does EU law require that the domestic legislation be interpreted or disapplied in a manner which provides GL with an option to defer the payment of tax;

(b) if so, does EU law require that the domestic legislation be interpreted or disapplied in a manner which provides GL with an option to defer the payment of tax until the assets are disposed of outside the sub-group of which the company resident in the other Member State is parent (i.e. “on a realisation basis”) or is an option to pay tax in instalments (i.e. “on an instalment basis”) capable of providing a proportionate remedy;

(c) if, in principle, an option to pay tax by instalments is capable of being a proportionate remedy:

i. is that only the case if domestic law contained the option at the time of the disposals of assets, or is it compatible with EU law for such an option to be provided by way of remedy after the event (namely for the national court to provide such an option after the event by applying a conforming construction or disapplying the legislation);

ii does EU law require national courts to provide a remedy which interferes with the relevant EU law freedom to the least possible extent, or is it sufficient for the national courts to provide a remedy which, whilst proportionate, departs from the existing national law to the minimum extent possible;

iii. what period of instalments is necessary; and

iv. is a remedy involving an instalment plan in which payments fall due prior to the date on which the issues between the parties are finally determined in breach of EU law, i.e. must the instalment due dates be prospective?’

Judgment

The CJEU (Third Chamber) ruled as follows:

- Article 63 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that national legislation which applies only to groups of companies does not fall within its scope.

- Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that national legislation which imposes an immediate tax charge on a disposal of assets from a company which is resident for tax purposes in a Member State to a sister company which is resident for tax purposes in a third country and which does not carry on a trade in that Member State through a permanent establishment, where both of those companies are subsidiaries wholly owned by a common parent which is resident for tax purposes in another Member State, does not constitute a restriction on the freedom of establishment, within the meaning of Article 49 TFEU, of that parent company, in circumstances where such a disposal would be made on a tax-neutral basis if the sister company were also resident in the first Member State or carried on a trade there through a permanent establishment.

- Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that a restriction of the right to freedom of establishment resulting from the difference in treatment between national and cross-border disposals of assets for consideration within a group of companies under national legislation which imposes an immediate tax charge on a disposal of assets by a company resident for tax purposes in a Member State may, in principle, be justified by the need to maintain a balanced allocation of the power to impose taxes between the Member States, without it being necessary to provide for the possibility of deferring payment of the charge in order to guarantee the proportionality of that restriction, where the taxpayer concerned has obtained, by way of consideration for the disposal of the assets, an amount equal to the full market value of those assets.

Legal context

The withdrawal agreement

3 The Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community (OJ 2020 L 29, p. 7; ‘the withdrawal agreement’) was approved by Council Decision (EU) 2020/135 of 30 January 2020 (OJ 2020 L 29, p. 1).

4 According to the preamble to the withdrawal agreement, EU law in its entirety ceases, subject to the arrangements laid down in that agreement, to apply to the United Kingdom from the date of entry into force of that agreement.

5 The withdrawal agreement provides, in Article 126 thereof, for a transition period, starting on the date of entry into force of that agreement and ending on 31 December 2020, during which EU law is applicable to the United Kingdom, unless otherwise provided for in that agreement.

6 Article 86 of the withdrawal agreement, entitled ‘Pending cases before the Court of Justice of the European Union’, provides, in paragraphs 2 and 3 thereof:

‘2. The Court of Justice of the European Union shall continue to have jurisdiction to give preliminary rulings on requests from courts and tribunals of the United Kingdom made before the end of the transition period.

3. For the purposes of this Chapter, … requests for preliminary rulings shall be considered as having been made, at the moment at which the document initiating the proceedings has been registered by the registry of the Court of Justice …’

7 Article 89(1) of the withdrawal agreement states:

‘Judgments and orders of the Court of Justice of the European Union handed down before the end of the transition period, as well as such judgments and orders handed down after the end of the transition period in proceedings referred to in Articles 86 and 87, shall have binding force in their entirety on and in the United Kingdom.’

8 Pursuant to Article 185 of the withdrawal agreement, that agreement entered into force on 1 February 2020.

United Kingdom law

9 Under Sections 2 and 5 of the Corporation Tax Act 2009 (‘the CTA 2009’) and Section 8 of the Taxation of Chargeable Gains Act 1992 (‘the TCGA 1992’), a company having its tax residence in the United Kingdom is chargeable to corporation tax on all its profits (including chargeable gains) accruing in the relevant accounting period.

10 In accordance with Section 5(3) of the CTA 2009, a company which does not have its tax residence in the United Kingdom but which carries on a trade there through a permanent establishment in the United Kingdom is chargeable to tax on the profits attributable to that permanent establishment. Moreover, under Section 10 B of the TCGA 1992, such a company is chargeable to tax on the chargeable gains that it accrues on disposal of assets if those assets are situated in the United Kingdom and are used for the purposes of carrying on a trade or for those of the permanent establishment. Those assets are referred to as ‘chargeable assets’ by Section 171(1A) of the TCGA 1992.

11 According to Sections 17 and 18 of the TCGA 1992, the disposal of an asset is deemed to be for consideration equal to the market value of those assets where the disposal is otherwise than by way of a bargain made at arm’s length or the disposal is made to a connected person.

12 Section 170 of the TCGA 1992 provides:

‘(1) This section has effect for the interpretation of sections 171 to 181 except in so far as the context otherwise requires …

(2) Except as otherwise provided—

…

(b) subsections (3) to (6) below apply to determine whether companies form a group and, where they do, which is the principal company of the group;

…

(d) “group” and “subsidiary” shall be construed with any necessary modifications where applied to a company incorporated under the law of a country outside the United Kingdom.

(3) Subject to subsections (4) to (6) below—

(a) a company (referred to below and in sections 171 to 181 as the “principal company of the group”) and all its 75 per cent. subsidiaries form a group and, if any of those subsidiaries have 75 per cent. subsidiaries, the group includes them and their 75 per cent. subsidiaries, and so on, but

(b) a group does not include any company (other than the principal company of the group) that is not an effective 51 per cent. subsidiary of the principal company of the group.

(4) A company cannot be the principal company of a group if it is itself a 75 per cent. subsidiary of another company.

…’

13 Section 171 of the TCGA 1992 and Sections 775 and 776 of the CTA 2009 (together, ‘the group transfer rules’) provide that a disposal of assets between group companies that are chargeable to corporation tax in the United Kingdom must take place on a tax-neutral basis.

14 Article 171 of the TCGA 1992 provides:

‘(1) Where—

(a) a company (“company A”) disposes of an asset to another company (“company B”) at a time when both companies are members of the same group, and

(b) the conditions in subsection (1A) below are met,company A and company B are treated for the purposes of corporation tax on chargeable gains as if the asset were acquired by company B for a consideration of such amount as would secure that neither a gain nor a loss would accrue to company A on the disposal.

(1A) The conditions referred to in subsection (l)(b) above are—

(a) that company A is resident in the United Kingdom at the time of the disposal, or the asset is a chargeable asset in relation to that company immediately before that time, and

(b) that company B is resident in the United Kingdom at the time of the disposal, or the asset is a chargeable asset in relation to that company immediately after that time.

For this purpose an asset is a “chargeable asset” in relation to a company at any time if, were the asset to be disposed of by the company at that time, any gain accruing to the company would be a chargeable gain and would by virtue of section 10B form part of its chargeable profits for corporation tax purposes.

…’

15 Section 775 of the CTA 2009 states:

‘(1) A transfer of an intangible fixed asset from one company (“the transferor”) to another company (“the transferee”) is tax-neutral for the purposes of this Part if—

(a) at the time of the transfer both companies are members of the same group,

(b) immediately before the transfer the asset is a chargeable intangible asset in relation to the transferor, and

(c) immediately after the transfer the asset is a chargeable intangible asset in relation to the transferee.

(2) For the consequences of a transfer being tax-neutral for the purposes of this Part, see section 776.

…’

16 Section 776 of the CTA 2009 provides:

‘(1) This section sets out the consequences of a transfer of an asset being “tax-neutral” for the purposes of this Part.

(2) The transfer is treated for those purposes as not involving—

(a) any realisation of the asset by the transferor, or

(b) any acquisition of the asset by the transferee.

(3) The transferee is treated for those purposes—

(a) as having held the asset at all times when it was held by the transferor, and

(b) as having done all such things in relation to the asset as were done by the transferor.

(4) In particular—

(a) the original cost of the asset in the hands of the transferor is treated as the original cost in the hands of the transferee, and

(b) all such credits and debits in relation to the asset as have been brought into account for tax purposes by the transferor under this Part are treated as if they had been brought into account by the transferee.

(5) The references in subsection (4)(a) to the cost of the asset are to the cost recognised for tax purposes.’

17 Section 764 of the CTA 2009 states:

‘(1) This Chapter applies for the purposes of this Part to determine whether companies form a group and, where they do, which is the principal company of the group.

…’

18 Section 765 of the CTA 2009 provides:

‘(1) The general rule is that—

(a) a company (“A”) and all its 75% subsidiaries form a group, and

(b) if any of those subsidiaries have 75% subsidiaries, the group includes them and their 75% subsidiaries, and so on.

(2) A is referred to in this Chapter and in Chapter 9 as the principal company of the group.

(3) Subsections (1) and (2) are subject to the following provisions of this Chapter.’

19 Section 767 of the CTA 2009 provides:

‘(1) The general rule is that a company (“A”) is not the principal company of a group if it is itself a 75% subsidiary of another company (“B”).

…’

20 Section 59D of the Taxes Management Act 1970 (‘the TMA 1970’) provides:

‘(1) Corporation tax for an accounting period is due and payable on the day following the expiry of nine months from the end of that period.

(2) If the tax payable is then exceeded by the total of any relevant amounts previously paid (as stated in the relevant company tax return), the excess shall be repaid.

…’

21 By virtue of Section 87A of the TMA 1970, interest is chargeable on unpaid tax from the date on which that tax is payable.

22 Under Sections 55 and 56 of the TMA 1970, where a decision of HMRC (including a partial closure notice) amending a company’s return for a particular accounting period has been the subject of an appeal to the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) (United Kingdom), payment of the tax charged may be postponed by agreement with HMRC or by application to the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber), such that the tax becomes payable only on determination of the appeal to that tribunal.

23 Article 13(5) of the Convention between the United Kingdom and the Swiss Confederation for the avoidance of double taxation, based on the Model Tax Convention of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on Income and on Capital, provides that gains from the alienation of assets, such as those concerned by the case in the main proceedings, are to be taxable only in the territory in which the alienator is resident.

The application to reopen the oral part of the procedure

42 Following the delivery of the Advocate General’s Opinion, GL, by document lodged at the Court Registry on 29 September 2022, applied for the oral part of the procedure to be reopened, pursuant to Article 83 of the Rules of Procedure of the Court.

43 In support of that application, GL submits, in essence, that the Advocate General misunderstood certain aspects of United Kingdom law and certain facts of the dispute in the main proceedings, which would justify the holding of a hearing.

44 In that regard, it should be noted at the outset that, under the second paragraph of Article 252 TFEU, it is the duty of the Advocate General, acting with complete impartiality and independence, to make, in open court, reasoned submissions on cases which, in accordance with the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union, require his or her involvement. The Court is not bound either by the Advocate General’s Opinion or by the reasoning on which it is based (judgment of 8 September 2022, Finanzamt R (Deduction of VAT linked to a shareholder contribution), C‑98/21, EU:C:2022:645, paragraph 29 and the case-law cited).

45 It should also be recalled that neither the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union nor the Rules of Procedure makes provision for interested parties to submit observations in response to the Advocate General’s Opinion. As a consequence, the fact that a party disagrees with the Advocate General’s Opinion, irrespective of the questions examined in the Opinion, cannot in itself constitute grounds justifying the reopening of the oral procedure (judgment of 8 September 2022, Finanzamt R (Deduction of VAT linked to a shareholder contribution), C‑98/21, EU:C:2022:645, paragraph 30 and the case-law cited).

46 By its arguments, GL appears to be seeking to respond to the Advocate General’s Opinion by calling into question certain of his assessments.

47 It is true that, pursuant to Article 83 of its Rules of Procedure, the Court may, at any time, after hearing the Advocate General, order the reopening of the oral part of the procedure, in particular if it considers that it lacks sufficient information or where a party has, after the close of that part of the procedure, submitted a new fact which is of such a nature as to be a decisive factor for the decision of the Court, or where the case must be decided on the basis of an argument which has not been debated between the parties or the interested persons referred to in Article 23 of the Statute of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

48 However, it must be held that the alleged errors of fact and of law invoked by GL do not justify the reopening of the oral part of the procedure.

49 First, as regards the alleged misunderstanding of national law, it should be noted that GL alleges an error of assessment based on a misinterpretation of the judgment of 13 March 2007, Test Claimants in the Thin Cap Group Litigation (C‑524/04, EU:C:2007:161). However, the fact that GL has a different interpretation of that judgment cannot constitute an error of assessment of the national legal framework, the description of which in points 7 to 14 of the Advocate General’s Opinion is not called into question by that company.

50 Second, as regards the alleged misunderstanding of certain facts in the main proceedings, it is sufficient to point out that the Advocate General’s analysis in his Opinion is based on the facts as communicated by the referring tribunal and set out in points 15 to 30 of that Opinion.

51 In those circumstances, the Court, after having heard the Advocate General, thus considers that it has all the necessary information available to it in order to answer the questions asked by the referring tribunal.

52 Accordingly, there is no need to order that the oral part of the procedure be reopened.

Consideration of the questions referred

The jurisdiction of the Court

53 It follows from Article 86 of the withdrawal agreement, which entered into force on 1 February 2020, that the Court is to continue to have jurisdiction, notwithstanding the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union on 31 January 2020, to give preliminary rulings on requests from courts and tribunals of the United Kingdom which were made before the end of the transition period set at 31 December 2020. This is so in the case of the present request for a preliminary ruling, which was received at the Court on 30 December 2020 (see, to that effect, judgment of 3 June 2021, Tesco Stores, C‑624/19, EU:C:2021:429, paragraph 17). It follows that the Court has jurisdiction to answer the questions referred for a preliminary ruling in the present case.

The first and second questions

54 By its first and second questions, which it is appropriate to examine together, the referring tribunal asks, in essence, whether Article 63 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that national legislation which applies only to groups of companies falls within its scope.

55 In that regard, it is clear from settled case-law that, in order to determine whether national legislation comes within the scope of one or other of the fundamental freedoms guaranteed by the FEU Treaty, the purpose of the legislation concerned must be taken into consideration (see, to that effect, judgment of 7 April 2022, Veronsaajien oikeudenvalvontayksikkö (Exemption of contractual investment funds), C‑342/20, EU:C:2022:276, paragraph 35 and the case-law cited).

56 The Court has held that national legislation intended to apply only to those shareholdings which enable the holder to exert a definite influence on a company’s decisions and to determine its activities falls within the scope of Article 49 TFEU. On the other hand, national provisions which apply to shareholdings acquired solely with the intention of making a financial investment without any intention to influence the management and control of the undertaking must be examined exclusively in light of the free movement of capital (judgment of 13 November 2012, Test Claimants in the FII Group Litigation, C‑35/11, EU:C:2012:707, paragraphs 91 and 92 and the case-law cited).

57 What is more, where a national measure relates to the freedom of establishment and the free movement of capital at the same time, in accordance with its settled case-law, the Court will in principle examine the measure in dispute in relation to only one of those two freedoms if it appears, in the circumstances of the case in the main proceedings, that one of them is entirely secondary in relation to the other and may be considered together with it (see, to that effect, judgment of 17 September 2009, Glaxo Wellcome, C‑182/08, EU:C:2009:559, paragraph 37 and the case-law cited).

58 Furthermore, it is apparent from the Court’s case-law that, in so far as any given national rules concern only relationships within a group of companies, they primarily affect the freedom of establishment (judgment of 26 June 2008, Burda, C‑284/06, EU:C:2008:365, paragraph 68 and the case-law cited).

59 In this instance, the legislation at issue in the main proceedings relates to the tax treatment of disposals of assets within the same group of companies. Likewise, it is apparent from the order for reference that the group transfer rules apply only to disposals made within a group of companies, the concept of ‘group of companies’ being defined by the national legislation at issue in the main proceedings as referring to a company and its 75% subsidiaries as well as those subsidiaries’ 75% subsidiaries.

60 Moreover, as the United Kingdom Government submits, it appears that the group transfer rules apply only to disposals of assets between a parent company and the subsidiaries (or sub-subsidiaries) over which it exerts definite direct (or indirect) influence and to disposals of assets between sister subsidiaries (or sub-subsidiaries) which have a common parent company exercising definite influence on them. In both scenarios, the group transfer rules thus seem to apply because of the parent company’s holding in the capital of its subsidiaries, which allows it to exert definite influence over its subsidiaries.

61 Should the said rules have restrictive effects on the free movement of capital, those effects would be the unavoidable consequence of such an obstacle to freedom of establishment as there might be, and do not therefore justify an independent examination of those rules from the point of view of Article 63 TFEU (see, to that effect, judgment of 18 July 2007, Oy AA, C‑231/05, EU:C:2007:439, paragraph 24 and the case-law cited).

62 Accordingly, national legislation, such as the group transfer rules, which applies only to groups of companies, falls predominantly within the scope of Article 49 TFEU, which guarantees freedom of establishment, without it being necessary to examine it in the light of the free movement of capital guaranteed by Article 63 TFEU.

63 Furthermore, it should be recalled that Article 63 TFEU cannot, in any event, be applied in a situation which would, in principle, fall within the scope of Article 49 TFEU, where one of the companies concerned is established for tax purposes in a third country, which is the case of the Swiss company in the context of the 2011 disposal.

64 Since the Treaty does not extend freedom of establishment to third countries, it is important to ensure that the interpretation of Article 63(1) TFEU as regards relations with those states does not enable economic operators who do not fall within the territorial scope of freedom of establishment to profit from that freedom (judgment of 24 November 2016, SECIL, C‑464/14, EU:C:2016:896, paragraph 42 and the case-law cited).

65 There is therefore no need to examine, in addition, the applicability of Article 63 TFEU as referred to in the wording of the second question.

66 In the light of all the foregoing considerations, the answer to the first and second questions is that Article 63 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that national legislation which applies only to groups of companies does not fall within its scope.

The third question

67 By its third question, the referring tribunal asks, in essence, whether Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that national legislation which imposes an immediate tax charge on a disposal of assets from a company which is resident for tax purposes in a Member State to a sister company which is resident for tax purposes in a third country and which does not carry on a trade in that Member State through a permanent establishment, where both of those companies are subsidiaries wholly owned by a common parent which is resident for tax purposes in another Member State, constitutes a restriction on the freedom of establishment, within the meaning of Article 49 TFEU, of that parent company, in circumstances where such a disposal would be made on a tax-neutral basis if the sister company were also resident in the first Member State or carried on a trade there through a permanent establishment.

68 As a preliminary point, it should be noted, as did the Advocate General in points 41 and 42 of his Opinion, first, that the third question refers only to the type of transaction corresponding to the 2011 disposal, namely a disposal of assets from a company chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom to a company having its tax residence in a third country, in this instance in Switzerland, and which is not chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom.

69 Second, that question relates to a situation in which a parent company, in this instance the Netherlands company, has exercised its freedom under Article 49 TFEU by establishing a subsidiary in the United Kingdom, in this instance GL.

70 According to the Court’s settled case-law, freedom of establishment, which Article 49 TFEU grants to EU nationals, includes, in accordance with Article 54 TFEU, for companies or firms formed in accordance with the law of a Member State and having their registered office, central administration or principal place of business within the European Union, the right to exercise their activity in other Member States through a subsidiary, branch or agency (see, to that effect, judgment of 22 September 2022, W (Deductibility of final losses of a non-resident permanent establishment), C‑538/20, EU:C:2022:717, paragraph 14 and the case-law cited).

71 Freedom of establishment aims to ensure that nationals of other Member States and the companies referred to in Article 54 TFEU receive the same treatment as nationals of the host Member State, by prohibiting any discrimination based on the place in which companies have their seat (judgment of 6 October 2022, Contship Italia, C‑433/21 and C‑434/21, EU:C:2022:760, paragraph 34 and the case-law cited).

72 As the Advocate General stated in point 45 of his Opinion, national legislation, such as the group transfer rules, does not entail any difference in treatment according to the place of tax residence of the parent company, since it treats a United Kingdom-tax-resident subsidiary of a parent company having its seat in another Member State in the same way as it treats a United Kingdom-tax-resident subsidiary of a parent company having its seat in the United Kingdom. In the case at hand, it thus appears that GL would have received the same tax treatment if the parent company – the Netherlands company – had had its tax residence in the United Kingdom.

73 It follows that such national legislation does not treat a subsidiary of a company resident for tax purposes in a Member State less favourably than a comparable subsidiary of a company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom.

74 Accordingly, such legislation does not entail any restriction on the freedom of establishment of the parent company.

75 That conclusion cannot be overturned by the arguments put forward by GL. In its view, the inability to transfer assets from GL, a company resident in the United Kingdom acquired by the Netherlands company, to a subsidiary of the latter on a tax-neutral basis would have made the acquisition of GL by the Netherlands company less attractive and would likely have dissuaded it from making that acquisition.

76 In that regard, it should be pointed out that the case-law on which GL relies, according to which there is a restriction on freedom of establishment when a measure renders ‘less attractive the exercise of [that] freedom’ covers situations which are different from that at issue in the main proceedings, namely situations where a company seeking to exercise its freedom of establishment in another Member State suffers a disadvantage by comparison with a similar company which does not exercise that freedom (see, to that effect, judgment of 29 November 2011, National Grid Indus, C‑371/10, EU:C:2011:785, paragraphs 36 and 37).

77 However, in the present case, the group transfer rules impose an immediate tax liability on the disposal of assets by a UK-tax-resident subsidiary of a parent company not resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom to a third country and impose the same tax liability in the comparable situation of a disposal of assets by a UK-tax-resident subsidiary of a parent company resident for tax purposes in the United Kingdom to a third country.

78 In the light of all the foregoing considerations, the answer to the third question is that Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that national legislation which imposes an immediate tax charge on a disposal of assets from a company which is resident for tax purposes in a Member State to a sister company which is resident for tax purposes in a third country and which does not carry on a trade in that Member State through a permanent establishment, where both of those companies are subsidiaries wholly owned by a common parent which is resident for tax purposes in another Member State, does not constitute a restriction on the freedom of establishment, within the meaning of Article 49 TFEU, of that parent company, in circumstances where such a disposal would be made on a tax-neutral basis if the sister company were also resident in the first Member State or carried on a trade there through a permanent establishment.

The fourth question

79 As the fourth question is asked in the alternative, that is to say, only in the event that the Court answers the first and second questions in the affirmative as regards the applicability, in the case at hand, of Article 63 TFEU, there is no need to answer this question.

The fifth question

80 By its fifth question, the referring tribunal asks, in essence, whether Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that a restriction of the right to freedom of establishment resulting from the difference in treatment between national and cross-border disposals of assets for consideration within a group of companies under national legislation which imposes an immediate tax charge on a disposal of assets by a company resident for tax purposes in a Member State may, in principle, be justified by the need to maintain a balanced allocation of the power to impose taxes between the Member States, without it being necessary to provide for the possibility of deferring payment of the charge in order to guarantee the proportionality of that restriction, where the taxpayer concerned has obtained, by way of consideration for the disposal of the assets, an amount equal to the full market value of those assets.

81 As a preliminary point, it should be noted that there is no need to answer this question in the context of the 2011 disposal. First, according to the answer given to the third question, legislation such as the group transfer rules does not entail any restriction on the freedom of establishment of the parent company. Second, as regards a possible restriction on GL’s freedom of establishment, it must be pointed out that a disposal of assets by a company chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom to a company resident for tax purposes in Switzerland and which is not chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom does not fall within the scope of Article 49 TFEU, given that the Swiss Confederation is not a Member State. The FEU Treaty does not extend the freedom of establishment to third countries nor does the scope of Article 49 TFEU extend to situations concerning the establishment of a company of a Member State in a third country (see, to that effect, order of 10 May 2007, A and B, C‑102/05, EU:C:2007:275, paragraph 29).

82 So far as concerns the 2014 disposal, in the context of which GL disposed of shares in a subsidiary to the Netherlands company, it is common ground that the group transfer rules give rise to different tax treatment for companies chargeable to United Kingdom corporation tax which make intra-group disposals of assets, depending on whether the disposal in question is to a British company or to a company established in a Member State. Although no tax charge arises where such a company disposes of assets to a group company chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom, those rules do not provide for such an advantage when, as in the context of the 2014 disposal, the disposal is to a group company chargeable to tax in a Member State.

83 It follows that such rules constitute a restriction on freedom of establishment in so far as they lead to less favourable tax treatment of companies chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom which carry out disposals of intra-group assets to companies which are not chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom compared to companies chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom which carry out disposals of intra-group assets to companies chargeable to tax in the United Kingdom.

84 The referring tribunal appears to accept that such a restriction may be justified by overriding reasons in the public interest, namely the need to maintain the balanced allocation of the power to impose taxes between the Member States.

85 According to the United Kingdom Government, the Court has recognised that the maintenance of a balanced allocation of taxing powers between the Member States can, in principle, justify a difference in treatment between cross-border transactions and transactions carried out within the same tax jurisdiction. That government is of the view that the national measures at issue in the main proceedings pursue such an objective, are proportionate and do not go beyond what is necessary to attain their objective.

86 As the Court has repeatedly held, the justification based on the need to maintain the balanced allocation of the power to impose taxes between the Member States can be accepted where the system in question is designed to prevent situations which are liable to jeopardise the right of a Member State to exercise its power to tax in relation to activities carried out in its territory (see, to that effect, judgment of 20 January 2021, Lexel, C‑484/19, EU:C:2021:34, paragraph 59 and the case-law cited).

87 However, the legislation at issue in the main proceedings and the restriction which it entails should not go beyond what is necessary to attain that objective (see, to that effect, judgment of 8 March 2017, Euro Park Service, C‑14/16, EU:C:2017:177, paragraph 63 and the case-law cited).

88 As the Advocate General stated in point 62 of his Opinion, the only question on which the parties to the main proceedings disagree concerns the proportionate nature, by reference to that objective, of the immediate chargeability of the tax in question, without there being an option of deferring payment. The referring tribunal’s question seems to relate, in reality, to the consequence flowing from the fact that GL is excluded from the benefit of the tax exemption by the group transfer rules, in other words the fact that the amount of the tax due is immediately chargeable.

89 In that connection, it is apparent from the case-law of the Court that Member States entitled to tax capital gains generated by disposals of assets when the assets in question were on their territory have the power to make provision for a taxable event other than the actual realisation of those gains, in order to ensure that those assets are taxed (see, to that effect, judgment of 21 May 2015, Verder LabTec, C‑657/13, EU:C:2015:331, paragraph 45). It appears that a Member State may thus impose a tax charge in respect of the unrealised capital gains in order to ensure that those assets are taxed.

90 However, legislation of a Member State which requires the immediate recovery of the tax due in respect of the unrealised capital gains generated in the context of its fiscal jurisdiction, at the time of the transfer of the place of effective management of a company to a place outside its territory has been held to be disproportionate by reason of the fact that measures existed which were less restrictive of the freedom of establishment than the immediate recovery of that tax. In that regard, the Court has held that it was appropriate to give the taxable person the choice between, on the one hand, immediate payment of that tax, and, on the other hand, deferred payment of that tax, together with, if appropriate, interest in accordance with the applicable national legislation (judgment of 16 April 2015, Commission v Germany, C‑591/13, EU:C:2015:230, paragraph 67).

91 In that context, as the Advocate General stated in point 68 of his Opinion, when it comes to distinguishing the capital gains realised by the transferor of the assets within a group of companies from unrealised capital gains, two circumstances are particularly relevant, the first being the fact that all cases of exit taxes are characterised by the liquidity problem faced by a taxpayer who must pay a tax on a capital gain which he or she has not yet realised, the second being the fact that the tax authorities must ensure the tax on the capital gains realised during the period the assets were within their tax jurisdiction is paid (see, to that effect, judgment of 29 November 2011, National Grid Indus, C‑371/10, EU:C:2011:785, paragraph 52) and that the risk the tax will not be paid may increase with the passage of time (see, to that effect, judgments of 29 November 2011, National Grid Indus, C‑371/10, EU:C:2011:785, paragraph 74, and of 21 May 2015, Verder LabTec, C‑657/13, EU:C:2015:331, paragraph 50).

92 In the case of a capital gain realised as a result of a disposal of assets, however, the taxpayer does not, in principle, face a liquidity problem and can pay the capital gains tax with the proceeds of that disposal of assets. In the case at hand, it is apparent from the order for reference and from the actual wording of the fifth question that, as far as the 2014 disposal is concerned, it is common ground that GL received, by way of consideration for it, remuneration corresponding to the market value of the assets concerned by that disposal. Consequently, the capital gains in respect of which GL was chargeable to tax corresponded to the capital gains realised.

93 Thus, in circumstances where, first, capital gains were realised at the time of the taxable event, second, the tax authorities must ensure the tax on the capital gains realised during the period the assets are within their tax jurisdiction is paid and, last, the risk the tax will not be paid may increase with the passage of time, an immediately recoverable tax charge appears proportionate to the objective of maintaining a balanced allocation of the power to impose taxes between the Member States, without the possibility of deferring payment having to be granted to the taxpayer.

94 In the light of all the foregoing considerations, the answer to the fifth question is that Article 49 TFEU must be interpreted as meaning that a restriction of the right to freedom of establishment resulting from the difference in treatment between national and cross-border disposals of assets for consideration within a group of companies under national legislation which imposes an immediate tax charge on a disposal of assets by a company resident for tax purposes in a Member State may, in principle, be justified by the need to maintain a balanced allocation of the power to impose taxes between the Member States, without it being necessary to provide for the possibility of deferring payment of the charge in order to guarantee the proportionality of that restriction, where the taxpayer concerned has obtained, by way of consideration for the disposal of the assets, an amount equal to the full market value of those assets.

The sixth question

95 In view of the answer given to the fifth question, there is no need to answer the sixth question.

Costs

96 Since these proceedings are, for the parties to the main proceedings, a step in the action pending before the national court, the decision on costs is a matter for that court. Costs incurred in submitting observations to the Court, other than the costs of those parties, are not recoverable.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info

Follow International Tax Plaza on Twitter (@IntTaxPlaza)