On June 29, 2023 on the website of the Dutch Courts the judgment of the Court of Appeal of Amsterdam (hereafter: the Court) in Case 22/00232, ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2023:1399, was published. In the underlying case the taxpayer and the tax authorities are disputing whether or not the taxpayer is allowed to divide the goodwill it acquired via an international legal merger into 2 parts and to capitalize one of these parts on the balance sheet of its Dutch head office and subsequently take amortization costs into account for Dutch corporate income tax purposes with respect to this capitalized goodwill.

In the underlying case the Dutch taxpayer and his advisers were very creative in their efforts to create tax deductible goodwill amortization costs.

Facts

As we understand all the steps described below have taken place within a few days in the financial year 2016.

Step 1

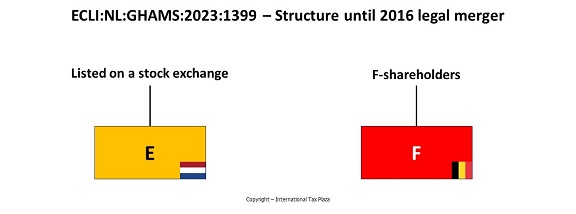

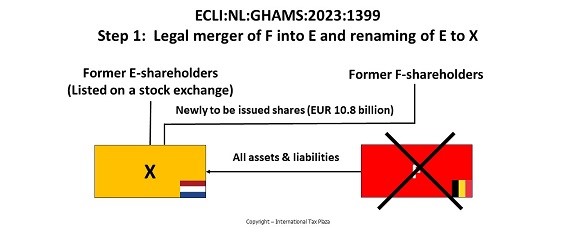

E is a Dutch resident company that is listed on a stock exchange. F was a Belgian resident company, which was also listed on a stock exchange. In 2016 E and F legally merged in accordance with Directive 2005/56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 October 2005 on cross-border mergers of limited liability companies, as implemented in Dutch and Belgian law.

As a result of a cross-border legal merger (the merger) all assets, liabilities and all legal relationships of the disappearing company (F) have been transferred under universal title to the acquiring legal entity (E). The shareholders of the disappearing legal entity (F) have become shareholders of the acquiring legal entity (E). F was dissolved by the merger without liquidation and ceased to exist. In the context of the merger E has been renamed X (X is the taxpayer in the underlying case).

As part of the aforementioned merger, X issued new ordinary shares to the former shareholders of F. In total, X has issued new shares with a total stock market value of EUR 10,765,446,851 (the merger price) to the former shareholders of F.

Step 2

By operations of law a (new) branch of X was opened in Belgium. All assets, liabilities and all legal relationships that formerly belonged to F have been allocated to this Belgian branch. The branch only existed for one single day Both for Dutch and Belgian tax purposes the Belgian branch qualifies as a permanent establishment.

Step 3

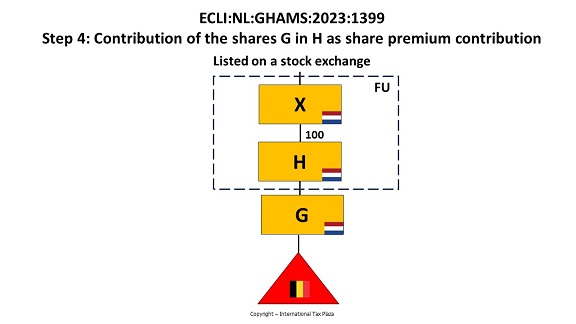

A day later, all the assets, liabilities and all legal relationships that formerly belonged to F and that were allocated to the branch/permanent establishment were legally demerged from X and transferred under universal title to the newly incorporated G BV. G BV is a Dutch resident 100% subsidiary of X.

Step 4

Subsequently all shares in G were transferred by means of a share premium contribution to H. H is a Dutch resident 100% subsidiary of X. X was incorporated in 2016. Since its incorporation X has been part of the fiscal unity for Dutch corporate income tax purposes of which X is the parent company.

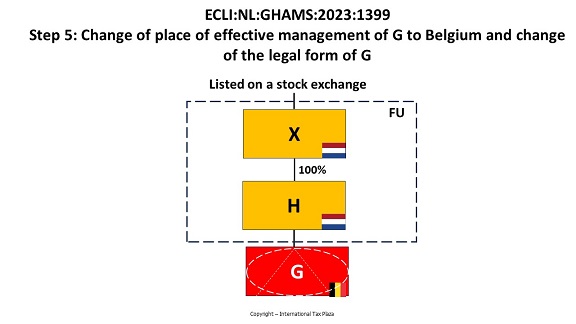

Step 5

The effective management of G is moved to Belgium. Subsequently the legal form of G was changed into a commanditaire vennootschap op aandelen (Limited partnership on shares) under Belgian law.

The goodwill

The X-Group paid more than market value of the assets minus the liabilities of the F-Group to obtain the business of the F-group. X is of the opinion that the difference between the purchase price it paid and the sum of the value of the assets and liabilities that X obtained through the merger, qualifies as (what X calls) synergy goodwill. According to X the total goodwill amounts to EUR 5,957 million.

X is of the opinion that at the moment of the merger the full amount of EUR 5,957 million of goodwill is to be capitalized on its balance sheet for corporate income tax purposes. According to X when subsequently the legal demerger takes place (Step 3) the EUR 5,957 million of goodwill is to be divided in an amount of EUR 2,394 million of synergy goodwill that is to be allocated to the old E-Group enterprise and EUR 3,563 million of internal goodwill that is to be allocated to the old F-Group enterprise. X is also of the opinion that after the legal demerger the EUR 2,394 million of synergy goodwill remains at the tax balance sheet of X.

X is of the opinion that the EUR 2,394 million of synergy goodwill that is allocated to the E-Group entities is subsequently to be allocated to 3 countries:

|

The Netherlands |

EUR 928,160,000 |

|

Country 1 |

EUR 37,087,000 |

|

Country 2 |

EUR 1,428,799,000 |

|

Total |

EUR 2,394,046,000 |

X based the abovementioned allocation of the synergy goodwill on how the activities in the different jurisdictions are expected to benefit from synergy benefits. In this respect X stated a.o. the following:

“The additional profit capacity created as a result of the merger is mainly related to savings still to be achieved on the merger date (synergy benefits) that are expected to be realized by the merger. The identified synergy benefits are diverse in nature and mainly include the following benefits:

- purchasing benefits on branded and private label products;

- purchasing benefits on fresh goods;

- purchase benefits on NFR products (“Not For Resale”, such as inventory, refrigerators, shopping carts and cash register systems);

- savings in the supply chain, and

- savings in overheads (e.g. IT and head office costs).”

For Dutch corporate income tax (DCIT) purposes X uses a straight-line 10-year amortization basis for the EUR 928 million synergy goodwill that relates to the Netherlands. The annual amortization costs to be taken into account for DCIT purposes therefore amount to EUR 92,816,000 (EUR 928,160,000/10). Because the legal merger between X, which was then still named E, and F took place during the course of the financial year 2016, for the year 2016 X took an amount of EUR 40,679,452 (EUR 92.800.000 X 160/365) into account as deductible amortization costs.

The Dutch tax authorities did not agree with the taxpayer’s approach and denied the deduction. The taxpayer appealed against the tax authorities’ decision. The Lower Court of Noord-Holland agreed with the Dutch tax authorities and denied the appeal and therewith the deduction of the goodwill amortization costs. The taxpayer appealed against the decision of the Lower Court of Noord-Holland.

The dispute

X and the Dutch tax authorities are disputing whether or not the DCIT assessment for the year 2016 has been raises for a too high amount. More specifically, they are disputing (as they were also disputing in first instance):

a. whether due to the legal merger (hereafter: the merger) the taxpayer is allowed to capitalize an amount of goodwill on the tax balance sheet of its head office, which the taxpayer can then amortize against its taxable profit for the years 2016 and onwards;

b. or whether, if due to the merger the taxpayer is allowed to capitalize goodwill on the tax balance of its head office, this capitalized goodwill as a result of the demerger has been transferred to the split-off entity (G) and has therefore disappeared from the tax balance sheet of X;

in case question a is answered in the affirmative and question b is answered in the negative, X is permitted to capitalize an amount of goodwill on its tax balance. In that case the question is:

c1. what is the amount of the goodwill that X can capitalize; and

c2. whether the goodwill can be amortized on a straight-line basis over 10 years and whether the amortization costs can be deducted from X’s Dutch taxable income.

From the considerations of the Court of Appeal

The Court is of the opinion that since that the merger price (the stock market price of the newly issued shares in E that were issued to the (former shareholders) of F is higher than the sum of the value of the acquired assets and liabilities, the difference is to be considered to constitute goodwill. The Court therefore concludes that the merger has created goodwill.

In the opinion of the Court, in the legal merger of the underlying case this goodwill consists of the difference between the market value of the assets and liabilities of the company of F obtained in the merger and the market value (on the merger date) of the ordinary shares E (later renamed X) granted in exchange for the common shares F as the disappearing company.

Furthermore, the Court concludes that this goodwill qualifies as acquired goodwill and not as homegrown goodwill. This conclusion is important since a taxpayer in the Netherlands is only allowed to take into account goodwill amortization costs with respect to acquired goodwill.

According to the Court the legal merger resulted in all assets and liabilities acquired under universal title from F were at the time of the merger being allocated to the branch opened by X. For tax purposes this branch constitutes a permanent establishment in Belgium. In the opinion of the Court, it has therefore been established that the entire assets that have been transferred to X by means of the legal merger consist exclusively of assets and liabilities (and related goodwill) located in Belgium. It is therefore also established that none of the assets and liabilities acquired from F formed an (effective) part of the Dutch tax base at any time. According to the Court from a Dutch tax perspective, the cross-border legal merger resulted in X acquiring (for one day) a permanent establishment in Belgium, to which all assets and liabilities acquired under universal title have been allocated. The object exemption of Article 15e of the DCIT Act applies to the profit made through this permanent establishment.

Subsequently the Court of Appeal also discusses the matter of the synergy benefits. The Court concludes that in the underlying case any buyer would be able to realize the synergy benefits that X refers to in its arguments. Consequently the conclusion is that it regards non-buyer specific synergies. After all, other potential buyers would also be willing to pay a fee for these synergy benefits. Whereas according to the Court a commercial buyer, on the other hand, will by definition not pay for expected buyer-specific synergies.

In the opinion of the Court, such compensation for the added value that is closely related to the assets and liabilities of a company that is to be merged with its own company and where it is plausible that any comparable third party would also be willing to pay this compensation, should be qualified for tax purposes as goodwill attached to the relevant assets and liabilities. Such goodwill should be regarded as a non-divisible residual item of what has been paid in excess of the sum of the value of the individual assets. Since it is likely that this amount constitutes a compensation for the added value enclosed in the assets and liabilities of (the former) F, for which any third party comparable to X would also have paid this compensation, in the opinion of the Court in the underlying case this means that the amount of EUR 5,926,000,000 should be regarded as such non-divisible goodwill for tax purposes,. Since such goodwill is closely related to the assets and liabilities belonging to the Belgian permanent establishment. The goodwill can therefore not be divided and partly be capitalized on the tax balance sheet of the head office.

In this respect the Court agrees with the tax inspector that the concepts of 'expected synergy benefits' and the tax concept of 'goodwill' cannot be equated. The circumstance that as a result of the merger, cost savings (synergy benefits) can be achieved by the combination of the two enterprises which will lead not only to additional profits for the enterprise located in Belgium, but also for the Dutch enterprise, doesn’t mean that in the underlying case the goodwill included in the merger price becomes 'divisible' for tax purposes.

The Court also considers that even if the Court was to follow the position of X (that part of the goodwill included in the merger price could be divided and capitalized on the tax balance sheet of X’s head office) the Court is of the opinion that this amount of goodwill after the legal demerger cannot in any event have remained on the tax balance sheet of X. In this respect the Court considers that the value of the assets and liabilities of F, which were acquired under universal title by means of the legal merger and the value of the same assets and liabilities, which were legally demerged only one day later is the same, namely EUR 10,765,000,000. After all, both values, both the merger price and the value of the assets to be legally demerged, are the result of the same calculation of the (at that time estimated) value and the same exchange ratio of shares E for one share F that has to be applied thereby. According to the Court this value therefore also includes the full amount of goodwill that was included in the merger price. With the circumstance brought forward by X that it appears from the demerger proposal and the demerger deed that it was the intention of the parties to operate the enterprise of F after the merger and the subsequent demerger in the same way as it was operated before the merger, it has not been made plausible that as a result an amount of EUR 2,394,000,000 of goodwill was not transferred to G together with the demerged assets (the entire company of the former F). In addition, X has not brought forward any plausible facts or circumstances from which it could follow that the fair market value of the merged and subsequently demerged enterprise would have decreased in one single day with an amount of EUR 2,394,000,000, or with an amount of EUR 928,000,000, or with any other amount.

Consequently, the Court of Appeal has denied X’s appeal and has denied X the possibility to take into account any amortization costs with respect to the goodwill for Dutch corporate income tax purposes.

Remarks ITP

We found it remarkable to see that in the alternative the Dutch tax authorities did not take the position that if its arguments failed the Fraus Legis (Abuse of Law) doctrine should apply to the underlying case. Reason herefor is that in our view the way the merging of the 2 groups is organized is very complicated, whereas it seems that the same result could be reached in a much simpler more straight forward way.

The questions that then has to be answered are:

1. Whether sound business reasons exist for the ultimate goal (the merging of the E and F groups) or whether the main purpose of the ultimate goal was to create a tax benefit? And

2. Whether sound business reasons exist for the way that was chosen to realize the ultimate goals, or whether one of the main purposes for choosing this way/transactions to realize the ultimate goal was to create a tax benefit?

In our view answering question 1 is simple. In the underlying case sound business reasons seem to exist for realizing the ultimate goal (the merging of the E and the F groups). The main purposes of the merging of the E and the F groups doesn’t seem to be to create a tax benefit.

Answering question 2 seems more difficult. As stated above it seems that the ultimate goal could also be realized in a much simpler manner. Namely by a share-for-share merger, followed by a change of the legal form of F. Looking at the fact that X wanted to capitalize part of the acquired goodwill on its Dutch tax balance and that it subsequently wanted to amortize this goodwill and take the amortization costs into account for Dutch corporate income tax purposes one can question whether this is not the main purpose for the complicated way in which the merging of the 2 groups was structures. It would then be up to the taxpayer, in the underlying case X, to make it plausible that creating a tax benefit was not one of the main purposes for the way the merging of the 2 groups was structured, but that sound business reasons were the reason for why the merging of the groups was structured in the way (true the 5 steps) as it was structured.

The full text of the judgment of the Court of Appeal of Amsterdam can be found here. (only available in the Dutch language)

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info

Follow International Tax Plaza on Twitter (@IntTaxPlaza)