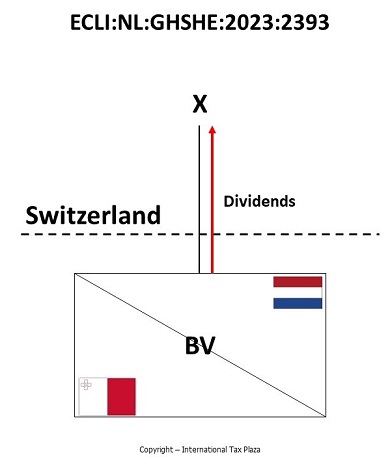

On July 31, 2023 on the website of the Dutch Courts an interesting judgment of the Court of Appeal of 's-Hertogenbosch on the (double) residency of a BV (a limited liability company) that was incorporated under Dutch law was published (Case numbers: BKDH-21/01014 up to and including BKDH-21/01020, ECLI:NL:GHSHE:2023:2393). The case is interesting because in its judgment the Court gives a refreshment course on the steps to be taken in order to determine the place of residence of a legal entity.

Simplified facts

In 2001 the taxpayer, a BV (a limited liability company), was incorporated under Dutch law by its sole shareholder X. As of its incorporation the taxpayer has been registered in the Dutch trade register. The registered office of the taxpayer is located in the Netherlands. With effect from 2010, the taxpayer moved its administrative seat to Malta. As of 2010, the taxpayer is registered with the Maltese Registry of Companies as 'Oversea Company'.

From 2010 onwards the Board of Directors has all the time consisted of X and a Maltese resident that was employed by a trust office. In the amended Articles of Association its is arranged that Board of Directors always contains at least as many Maltese residents as non-Maltese residents. Furthermore it is arranged that always a Maltese resident is appointed a President of the Board of Directors.

Until 2010 X has been resident of the Netherlands. As of 2010 X has been a resident of Switzerland. X owned a house in Switzerland. Furthermore X has a work/storage space with sanitary facilities in the Netherlands as well as an apartment in the Netherlands that is occupied by his mother. As of May 2011, X has access to a house in Portugal. In the years 2011-2014, X also owned two boats of which one has a berth in Portugal. X travels between these locations and once a year he attends the Shareholders meeting of the taxpayer in Malta.

For year X had a joined venture with C. Both X and C participated in the joined venture through their individual holding companies of which the taxpayer was X’s individual holding company. The shares in the joint venture company were sold in 2008. The buyer did not pay the purchase price in full. Both the taxpayer and C’s individual holding company granted the buyer a loan of 2 million euro with a maturity term of 7 years and an interest rate of 10%. The taxpayer and C’s individual holding company hold a priority share in the joint company.

The taxpayer’s activities consist out of the settlement of the aforementioned sale. Furthermore the more the taxpayer participates in several Dutch subsidiaries. In May 2011, the taxpayer acquired a 100% interest in Inc. Inc. is a company incorporated in Delaware (the United States) and a resident of Gibraltar. Inc.'s assets consist of the house in Portugal, which is available to X. Furthermore the assets of the taxpayer consist of loans, a securities portfolio and bank balances. The latter assets are partly invested with 2 Swiss banks. The agreements with these banks were made before the administrative seat of the taxpayer was moved to Malta. The banks have a mandate on the basis of which they can invest liquid assets without the intervention of the taxpayer.

The taxpayer does not have a bank account in Malta. The income it realized is therefore not 'remitted to Malta' (transferred or received). The annual accounts are audited by Mr D in Malta. From 2011 onwards the financial administration of the taxpayer is conducted by a trust office 2 in Malta. Until February 2012, [accountancy firm 1] from [location 1] was involved in the financial administration; from February 2012 onwards the financial administration up to and including the preparation of the 2010 annual accounts was conducted by [office] in [place 4].

The taxpayer has filed an 'Income Tax Return and Self Assessment' declaration in Malta for the years in question and has requested and received an exemption for the years 2011 and 2012 because of 'Foreign income not remitted to Malta'. In the Maltese tax return for the year 2013, the taxpayer stated its entire income in the so-called 'Untaxed Account'. The taxpayer’s Maltese taxable profit therefore amounted to nil in all of the underlying years.

In the years 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014 the taxpayer made dividend distributions to X. The dividend payments have been settled with the current account receivable from X. The taxpayer has not filed a dividend tax return for any of these dividend payments.

The dispute

The Dutch tax authorities and the taxpayer are arguing whether or not the Netherlands is allowed levy (corporate) income tax over X’s taxable incomes for the years 2011 through 2014 and to levy dividend withholding tax over the dividend distributions the taxpayer made in the years from 2011 through 2014.

The Dutch tax authorities are of the opinion that based on the tiebreaker rule as laid down in Article 4, Paragraph 4 of the Agreement between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and Malta for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on income and on capital (Hereafter: the Dutch-Maltese DTA) the taxpayer is deemed to be a resident of the Netherlands and that therefore the levying rights are allocated to the Netherlands.

The taxpayer’s primary position is that based on that same tiebreaker rule it is deemed to be a resident of Malta and that the Netherlands therefore has no right to either tax the profits of the taxpayer, nor the dividend distributions made by it. In the alternative, the taxpayer is of the opinion that based on the Dutch-Swiss DTA it is a resident of Switzerland as a result of which the Netherlands has no right to either tax the profits of the taxpayer nor the dividend distributions it made.

The approach of the Court of Appeal

In its judgment the Court of Appeal works methodically. First the Court establishes whether based on Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the DTAs the taxpayer is considered to be a resident of the Netherlands and of Malta respectively Switzerland. And only after that question is answered in the affirmative then the Court will continue with answering how the tiebreaker rule as included in the respective DTAs work out. But it was the theoretical approach that the Court takes to answer the first question that intrigued me.

The primary position of the taxpayer

The primary position of the taxpayer is that based on the tiebreaker rule as laid down in the Dutch-Maltese DTA it is deemed to be a resident of Malta. However, as stated above the tiebreaker rule only comes into play, if based on Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the DTA the taxpayer is considered to be a resident of both the Netherlands and Malta.

Article 4 of the Dutch-Maltese DTA

For as far as relevant Article 4 of the Agreement between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and Malta for the avoidance of double taxation and the prevention of fiscal evasion with respect to taxes on income and on capital reads as follows:

“1. For the purposes of this Agreement, the term “resident of one of the States” means any person who, under the law of that State, is liable to taxation therein by reason of his domicile, residence, place of management or any other criterion of a similar nature. The term does not include any person who is liable to tax in that State in respect only of income from sources therein or capital situated in that State.

(…)

4. Where by reason of the provisions of paragraph 1, a person other than an individual is a resident of both States, then it shall be deemed to be a resident of the State in which its place of effective management is situated.”

Is the taxpayer a resident of the Netherlands?

Obviously the first question that has to be answered is whether based on Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch Maltese DTA the taxpayer is considered to be a Dutch residen? Parties are not disputing this and they are agreeing that as a result of the residence fiction as laid down in Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the Dutch corporate income tax Act (In 2023 Article 2, Paragraph 5) based on Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Maltese DTA the taxpayer is considered to be a Dutch resident. Reason here for is that the fiction of Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the Dutch corporate income tax Act leads to an unlimited (domestic) tax liability in the Netherlands for corporate income tax purposes for bodies that, like the taxpayer, are incorporated under Dutch law. Article 2, Paragraph 5 of the Dutch corporate income tax Act reads as follows (2023 text):

“If the incorporation of a body has taken place under Dutch law, then for the purposes of this Act, with the exception of Articles 13 to 13d, 13i to 13k, 14a, 14b, 15 and 15a, the body is always deemed to be a resident of the Netherlands. In the case of a body that would not be a resident taxpayer without the application of the first sentence, the benefit stemming from a substantial interest as referred to in Article 17, Paragraph 3, under b, is determined on the basis of chapter III. A European public limited liability company that was governed by Dutch law at its incorporation is deemed to have been incorporated under Dutch law for the purposes of the first sentence.”

Is the taxpayer based on Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the DTA a resident of Malta?

Subsequently it is to be determined whether based on Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Maltese DTA the taxpayer is also considered to be a resident of Malta.

From the considerations of the Court:

“5.10 It must be stated first and foremost that when assessing the liability of a taxpayer to foreign tax, the tax inspector, and in appeal the court, must in principle ascertain itself of the content of the law of the foreign state. This is only different if a taxpayer is actually taxable as a resident in the other state, in which case it should be assumed that that taxpayer is subject to taxation as a resident under foreign laws. Unless either the tax inspector makes it plausible that the data on the basis of which the foreign tax authorities have assumed the residency of the person concerned under foreign law are incorrect or incomplete, or if the levy cannot reasonably be based on any rule of foreign law (HR May 12, 2006, ECLI :NL:HR:2006:AR5759, BNB 2007/38).

5.11 In the underlying years, the taxpayer has filed tax returns in Malta as a resident taxpayer. In the underlying years the taxpayer has not received any income or capital gains stemming from sources located in Malta. From the 'Income Tax Return and Self Assessment' forms completed by the interested party it appears that no Maltese tax was owed by the taxpayer.

5.12 The documents of the proceedings include acknowledgments of receipt of the aforementioned declaration forms from the Inland Revenue Department Malta. The Court also possses two documents from the Maltese tax authorities about the subjection to Maltese taxes of the taxpayer, namely: the letter of June 4, 2021 and the Certificate of Residence from 2015. From the documents referred to above, the Court deduces that the Maltese tax authorities regard the taxpayer as a resident - a so-called 'non-domiciled resident' - under Maltese tax law. The Court rejects the contrary view of the Inspector and therefore assumes that in the underlying years the taxpayer was subject to taxation in Malta.

5.13 The Court considers that the Inspector was not successful in the subsequent burden of proof that rests on him to demonstrate that either the information on the basis of which the Maltese tax authorities assumed that under Maltese law the taxpayer is a resident of Malta is incorrect or incomplete, or that the levy is not can reasonably be based on any rule of Maltese law.

5.14 The following can be derived from the database of Kluwer International Tax Law (section “Malta: Corporate Income Tax: Business Income and Expenses”) about the content of Maltese tax law:

“Basic rule

A Malta resident company is liable to corporation tax on income and capital gains arising or received in Malta or abroad. Tax is assessed and collected on all taxable income earned during the tax year.

(...)

Liability to tax

Generally, the Commissioner for Revenue may impose tax on the following categories of income and capital gains:

all income and capital gains arising in Malta

all income and capital gains, whether arising in or outside Malta to persons who are both ordinarily resident and domiciled in Malta

income arising outside Malta remitted to persons who are ordinarily resident in Malta but not domiciled in Malta, and

income arising outside Malta remitted to persons who are domiciled in Malta but not ordinarily resident in Malta.

Therefore, individuals and companies that are both ordinarily resident and domiciled in Malta are subject to income tax on their worldwide income, whether or not such income is remitted to Malta.

The income of individuals or companies who are ordinarily resident but not domiciled in Malta, or vice-versa, is subject to tax only on the portion of income received in Malta.

(...)

Residence

(…)

A company is considered to be resident in Malta for income tax purposes when the control and management of its business is exercised in Malta. Companies incorporated in Malta are automatically deemed to be resident and domiciled in Malta for tax purposes.

(…)

Domicile

Maltese law does not define the concept of domicile, which is treated consistently with established private international law principles. (…)”

5.15 The information mentioned above regarding the determination of the residency of companies is in accordance with Article 2, Paragraph 1 of the Maltese Income Tax Act:

“In this Act, and in any rules made under this Act, unless the subject or context otherwise requires

(…)

“resident in Malta” (…) when applied to a body of persons, means any body of persons the control and management of whose business are exercised in Malta, provided that a company incorporated in Malta on or after 1st July 1994 shall be resident in Malta (…)”.

5.16 From the aforementioned it follows that the taxpayer qualifies as a resident of Malta if its “control and management” are exercised in Malta. Referring to the judgment of the Dutch Supreme Court of July 2, 2021, ECLI:NL:HR:2021:1044, BNB 2021/156 (HR BNB 2021/156), the Inspector argues that the District Court rightly ruled that the Maltese concept “ control and management” is to be filled in materially, so that the absence of the actual management in Malta, as was established by the Inspector, means that there can be no question of residency in Malta as referred to in Article 4, paragraph 1, of the Dutch-Maltese DTA. According to the Inspector, the Maltese tax authorities would not have issued the Certificate of Residency if they had known that no substantive decision-making had taken place in Malta.

5.17 From the OECD website the Court derives the following information about the criteria used by Malta to determine whether "control and management" of a company takes place in Malta:

“Information on Residency for tax purposes

(…)

Section II – Criteria for Entities to be considered a tax resident

Generally, as per Article 2 of the Income Tax Act, an entity will be treated as a tax resident of Malta if it is incorporated in Malta. An entity incorporated outside Malta is considered resident in Malta only if the management and control of the entity is exercised in Malta. The term “management and control” is not defined in Maltese tax law, however in practice, in order to establish that management and control is in Malta, the Inland Revenue Department would take into account whether the board meetings of the company are held in Malta, whether general meetings are held in Malta, and whether any other decisions of the company are taken except at meetings in Malta. For dual resident entities, the residence of the entity may be determined by treaty.

(…)”

5.18 In the 2012 “Peer Review Report” of the OECD regarding Malta next to the information mentioned above the following is stated:

“Other features typically present to give substance to a claim of residency are that the company’s financial records are held and maintained in Malta with the audited financial statements prepared and filed in terms of the principles enunciated in Maltese company la[w], the majority of the directors are physically present in Malta to attend board meetings and some of the directors are resident in Malta.”

5.19 From this information, the Court deduces that the term “control and management” in Maltese tax law – apart from the starting point “whether any other decisions of the company are taken except at meetings in Malta” – has a fairly formal interpretation and, like the concept of “management and control” under Singapore law is broader than the concept of “place of management and control” in Article 3, Paragraph 4 of the Dutch-Singapore DTA of 19 February 1971 and the term “place of effective management” as it appeared in the OECD Model Conventions until 2017. The two latter expressions were at issue in the so-called Singapore judgments (Dutch Supreme Court January 19, 2018, ECLI:NL:HR:2018:47, BNB 2018/68 (HR BNB 2018/68), legal grounds 2.3.2 et seq., and HR BNB 2021/156), but the Court considers that case law, unlike the Inspector, irrelevant when assessing the question at issue here whether under Maltese law the taxpayer is a resident of Malta.

5.20 Since in the underlying case it amongst others has been established that the board meetings are held in Malta, the accounts are kept in Malta and some of the directors – one of the two – are residents of Malta, the Court deems it plausible that based on these established facts the Maltese tax authorities have been able to designate the taxpayer as a resident of Malta. In the opinion of the Court, based on the facts as brought forward by the Inspector it therefore cannot be concluded that the Maltese tax authorities would not have assumed the Maltese residency of the taxpayer. Let alone that designating the taxpayer as a resident of Malta not in reasonableness may be based on any rule of Maltese law.

5.21 The mentioned above in 5.14 about the taxation by Malta on income of companies that are “resident but not domiciled in Malta”, does raise the question whether that levy falls under the exception of the second sentence of Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Maltese DTA. After all, the levy seems to be limited to income from Maltese sources or assets located in Malta, which would mean that the requirement of "full tax liability" for the application of the first paragraph of the residence article has not been met. In the opinion of the Court, this question must be answered in the negative. After all, if foreign income is transferred to or received in Malta, the company in question will be taxed there on that income as a resident. The same applies if and insofar as amounts not initially transferred to, or received in Malta are subsequently transferred to, or received in Malta. If only in the latter case Maltese residency were to be assumed, this could result in a company being resident in Malta in one year and not in another year, which is a consequence that the Contracting States in the view of the Court could not have intended. Furthermore from the inclusion of the special provision in Article 2, Paragraph 5 of the Dutch-Maltes DTA the Court deduces that the contracting states wished to take the remittance base regime of Malta into account in a different way.

5.22 The conclusion is that the taxpayer in the underlying must be regarded as a resident of Malta within the meaning of Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Maltese DTA.”

The tiebreaker rule of Article 4, Paragraph 4 of the DTA

Since the Court came to the conclusion that based on the provision of Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Maltese DTA the taxpayer is a dual resident (both a resident of the Netherlands and of Malta) it has to be determined whether based on the tiebreaker rule of Article 4, Paragraph 4 of the Dutch-Maltese DTA the taxpayer is deemed to be resident of the Netherlands or of Maltese.

Based on case law the Court is of the opinion that the place where the effective management of an entity within the meaning of Article 4, Paragraph 4 of the Dutch-Maltese DTA is situated, is to be understood as the place where key decisions relating to the activities of the entity are taken, where the final responsibility for these decisions is borne and from where, where appropriate, instructions are given to the persons working within the entity. Consequently according to the Court who is in charge of the day-to-day management of the implementation of such decisions is not significant for the determination where the place of actual management of an entity is located.

Based on which activities of the taxpayer constitute the main activities of the taxpayer, as well as many e-mail correspondence between X and the Maltese Director of the taxpayer, X and Y, X and the auditor and meeting reports the Court comes to the conclusion that in the underlying case the place of effective management of the taxpayer is located within the Netherlands.

Does the Dutch-Swiss DTA limit the levying rights of the Netherlands

In the alternative the taxpayer has taken the position that is was a resident of Switzerland and that in that case the levying rights of the Netherlands for the years 2012 up to and including 2014 are limited by the Convention between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Swiss Confederation for the elimination of double taxation with respect to taxes on income and the prevention of tax evasion and avoidance as concluded in 2010 (Hereafter: the Dutch-Swiss DTA).

Residency under Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Swiss DTA

Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Swiss DTA reads as follows:

“For the purposes of this Convention, the term “resident of a Contracting State” means any person who, under the laws of that State, is liable to tax therein by reason of his domicile, residence, place of management or any other criterion of a similar nature, and also includes that State and any political subdivision or local authority thereof. This term, however, does not include any person who is liable to tax in that State in respect only of income from sources in that State.”

Is the taxpayer a resident of the Netherlands?

“5.40 Pursuant to Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Swiss DTA the taxpayer was a resident of the Netherlands if it was subject to tax there under the laws of the Netherlands by reason of her domicile, residence, place of management or any other similar circumstance. The second sentence of Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch Swiss DTA makes it clear that a person who is only subject to tax in that the Netherlands in respect of income from Dutch sources is not considered a resident of the Netherlands. For the application of this residence provision, the Court has previously held that in order to be a resident of one of the States, a person must be fully subject to the tax in that State ('full tax liability') (see Court of The Hague June 24, 2020, ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2020:1044, considerations 5.63-5.65).

5.41 Based on the residence fiction of Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the Dutch corporate income tax ACT (nowadays Article 2, Paragraph 5), the taxpayer was a resident of the Netherlands within the meaning of Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Swiss DTA. Since above it was concluded that for the application of the Dutch-Maltese DTA the taxpayer was a resident of the Netherlands, the full liability of the taxpayer in the Netherlands under Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Swiss DTA shall not be limited by the application of the Dutch-Maltese DTA.”

Is the taxpayer also a resident of Switzerland?

“5.42 The taxpayer took the position that pursuant to Article 4, Paragraph 1 of the Dutch-Swiss DTA she was also a resident of Switzerland. The taxpayer claims to be subject to Swiss taxation, given the residence there of its sole shareholder and co-director (x).

5.43 It has been established that the taxpayer has not actually been taxed in Switzerland, nor are there indications that the Swiss tax authorities regard the taxpayer as a Swiss resident.

5.44 Article 50 of the Swiss Bundesgesetz über die direkte Bundessteuer (DBG) (The Swiss Federal Law on Direct Federal Taxes) reads as follows:

“Persönliche Zugehörigkeit

Juristische Personen sind aufgrund persönlicher Zugehörigkeit steuerpflichtig, wenn sich ihr Sitz oder ihre tatsächliche Verwaltung in der Schweiz befindet.”

(Personal affiliation

Legal entities are subject to tax on the basis of personal affiliation if their registered office or effective management is in Switzerland)

5.45 The Court derives from the OECD website the following information about the criteria that are used by Switzerland to determine whether a company is a resident there for tax purposes:

“An entity is resident for tax purposes if its legal domicile (registered office) or place of effective management is located in Switzerland (the distinction between resident taxpayers and non-resident taxpayers corresponds to the distinction between unlimited tax liability and limited tax liability). The residence of an entity is determined by its formal place of incorporation. Therefore, if the legal domicile is in Switzerland, it is treated as a Swiss resident entity. The legal domicile is determined by the place where the entity is registered in the commercial registry.

If an entity is incorporated outside Switzerland, it may nevertheless be a Swiss resident entity for tax purposes if its place of effective management is in Switzerland. The place where important decisions are taken is determinative. Whether an entity is subject to corporate income tax and capital tax is based on the respective evidence regarding the effective management in each individual circumstance. Therefore, if the manager of a company resides in the country in which the company has its legal domicile, but in fact merely follows the instructions of a Swiss shareholder, the Swiss tax authorities may consider the company to be a Swiss resident.”

5.46 Swiss law therefore uses the criteria of registered office (‘Sitz’) or effective management (‘tatsächliche Verwaltung’) as criteria for resident tax liability. It has been established that the registered office of the taxpayer is not in Switzerland.

5.47 In the opinion of the Court, against the motivated dispute by the Tax Inspector, the burden of bringing forward plausible facts and circumstances that justify the conclusion that its actual management is located in Switzerland lay on the taxpayer that argues that it is actually led in a country other than where its formal management is located. The mere circumstance that its sole shareholder and co-director lives in Switzerland is insufficient for this – partly in view of the changing places where this shareholder stays – (cf. Dutch Supreme Court July 2, 2021, ECLI:NL:HR:2021:1044, BNB 2021/156). Since the taxpayer has not put forward anything to substantiate its assertion, the conclusion is that taxpayer is a resident of the Netherlands for the purposes of the Dutch-Swiss DTA. In that case, it is – rightly so – not in dispute between the parties that the DTA does not limit the levying rights of the Netherlands and that the tax assessments that are being disputed have also been correctly imposed in that respect."

The full text of the judgment, including all the facts and circumstances, can be found here. (The judgment is only available in the Dutch language.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info

Follow International Tax Plaza on Twitter (@IntTaxPlaza)