On August 12, 2021, on the website of the Dutch Courts a very interesting judgment of the District Court of Gelderland (Rechtbank Gelderland) in the joined cases, AWB-19_6602 and AWB-19_6603, ECLI:NL:RBGEL:2021:2972, was published. The cases concern the Dutch fiscal unity regime. Actually, the cases concern 2 questions. The first question is whether in the underlying case through a restructuring that a.o. includes a legal merger the taxpayer gains access to the possibility to set off pre-consolidation losses of a fiscal unity against profits that are allocable to the business of an entity that was only included in the fiscal unity after the losses were already incurred and that has disappeared through a legal merger that took place within the fiscal unity? Or does the fraus legis doctrine apply and is the taxpayer therefore denied the possibility to set off these pre-consolidation losses against the profits that are allocable to the business of the entity that has disappeared through the legal merger? The second question regarding which the District Court rules is whether based on the principles of sound business practices a taxpayer is obliged to amortize goodwill?

I find the case very interesting, because based on the judgment of the District Court of Gelderland it seems that in the underlying case the taxpayer has found a creative way to get access to pre-consolidation losses. Even although the Dutch legislation contains numerous provisions that are meant to avoid that the fiscal unity regime is abused to lower the Dutch tax burden. Several of these provisions specifically aim at avoiding that the fiscal unity regime is abused in order to get access to pre-consolidation losses and therewith lowering the amounts of Dutch corporate income tax (DCIT) due in later years. Since in the Netherlands losses can only be carried forward for a maximum of 6 years (6 financial years) the judgment can be of help in situations where a taxpayer is afraid that its losses are going to expire unused. Therefore this judgment might not only be interesting, but also very useful to taxpayers if the judgment of the District Court is ultimately confirmed by the Dutch Supreme Court.

The basics of settlement of losses within the Dutch fiscal unity regime

The DCIT Act provides taxpayers with the possibility to form a fiscal unity upon request. By doing so the entities that are included in the fiscal unity - and which normally would be treated as separate taxpayers - are treated as if the are one single taxpayer for DCIT purposes. Within a financial year the results of all entities included in the fiscal unity are consolidated. In other words, if a member of the fiscal unity incurs a loss in a certain financial year, this loss is set off against the taxable profits that other members of the fiscal unity have realized in that same financial year. This is called horizontal settlement of losses.

Next to this horizontal settlement of losses there is also the vertical settlement of losses. Vertical settlement of losses is something that also happens with stand-alone taxpayers. Vertical loss settlement is the carrying forward or backward of tax losses. Within in the fiscal unity regime vertical settlement of losses can only take place after the horizontal settlement of losses has taken place.

As stated above the Dutch legislation contains a significant number of anti-abuse provisions that specifically relate to the fiscal unity regime. Many of these provisions try to avoid that the fiscal unity regime is abused for getting access to so-called pre-consolidation losses. Basically, 2 sorts of pre-consolidation losses exist:

1. Losses incurred by a fiscal unity before a ‘new’ entity/fiscal unity is included in the fiscal unity;

2. Losses incurred by an entity/other fiscal unity before this entity/other fiscal unity is included in an existing fiscal unity.

The underlying case is so interesting because the District Court has confirmed the taxpayer’s position that via a careful restructuring, which included a specific way of legally merging 2 entities, the taxpayer got access to the pre-consolidation losses of its fiscal unity. By doing so the taxpayer did not only lower the amounts of DCIT due for the financial years 2015 and 2016, but it also avoided that the pre-consolidation losses of the fiscal unity would expire unused.

A very basic example of what the anti-abuse provisions try to avoid

To get a quick understanding why I find the underlying judgment so interesting I will first quickly discuss on a very high level how the vertical loss settlement goes within a fiscal unity. I will also on a very high level discuss what the anti-abuse provisions (for as far as the relate to loss compensation) try to arrange. I will discuss this via a very simplified example.

Group A has several Dutch operating entities. In financial year 1 BV A and BV B are members of a fiscal unity. A third BV, BV C is a wholly owned subsidiary of BV A, but during financial year 1 BV C is not a member of the of the fiscal unity. As off financial year 2 BV C is also a member of the fiscal unity of which BV A is the parent entity.

|

Financial year 1 |

Result for DCIT |

Financial year 1 |

Result for DCIT |

DCIT due |

|

|

BV A |

-70 |

BV C |

20 |

5 |

|

|

BV B |

30 |

||||

|

Total fiscal unity |

-40 |

||||

|

Financial year 2 |

Result for DCIT |

||||

|

BV A |

-60 |

||||

|

BV B |

40 |

||||

|

BV C |

100 |

||||

|

Total fiscal unity |

80 |

Based on the figures above the incurred loss by the fiscal unity for the financial year 1 amounts to 40. Whereas the taxable profit realized during financial year 2 amounts to 80.

However, in financial year 2 BV C is a new member of the fiscal unity. Article 15ae, paragraph 1, sub c of the DCIT Act contains an anti-abuse provision for such situations. Article 15ae, paragraph 1, sub c of the DCIT Act reads as follows: “if an existing fiscal unity is expanded, or if an existing fiscal unity is included in a new fiscal unity – the settlement of a loss suffered by that existing fiscal unity before the consolidation date against the taxable profits of the fiscal unity takes place insofar as this profit can be allocated to the entities that belonged to the existing fiscal unity immediately prior to the consolidation date.”

So based on Article 15ae, paragraph 1, sub c of the DCIT Act the losses incurred by the fiscal unit in financial year 1 can only be set off against the taxable profits that BV A and BV B realized in financial year 2. So, in order to determine whether a vertical settlement of the loss incurred by the fiscal unity in financial year 1 can take place we need to answer the following questions:

· Did the fiscal unity realize a taxable profit in financial year 2? If “Yes”, go to question 2. If “No”, no vertical settlement of losses can take place. In this case the answer is “Yes”, so we go to question 2.

· Did BV A and BV B (the entities that were members of the fiscal unity in financial year 1) realize a combined taxable profit in financial year 2? If “Yes”, a vertical settlement of losses can take place. If “No”, no vertical settlement of losses can take place. In our example the answer is “No” so no vertical settlement of losses can take place.

· If the answer to question 2 is “Yes”, the combined taxable profit of BV A and BV B has to be determined. This is then the taxable profit against which the loss of financial year 1 can be set off.

Above we described the standard situation. However, the as stated above the District Court of Gelderland has confirmed the taxpayer’s position that through a carefully planned restructuring, which included a legal merger, the taxpayer has found a backdoor via which it could set off the losses that the fiscal unity of BV A and BV B incurred before it was expanded with BV C against the taxable profits realized through the business of BV C after BV C was included in the fiscal unity.

Case ECLI:NL:RBGEL:2021:2972

The facts

Unfortunately, the facts as included in the judgment of the Court do not mention the respective dates, but only states “Date”. In the description given below I assume that the facts as mentioned in the judgment of the Court are mentioned in the chronological order.

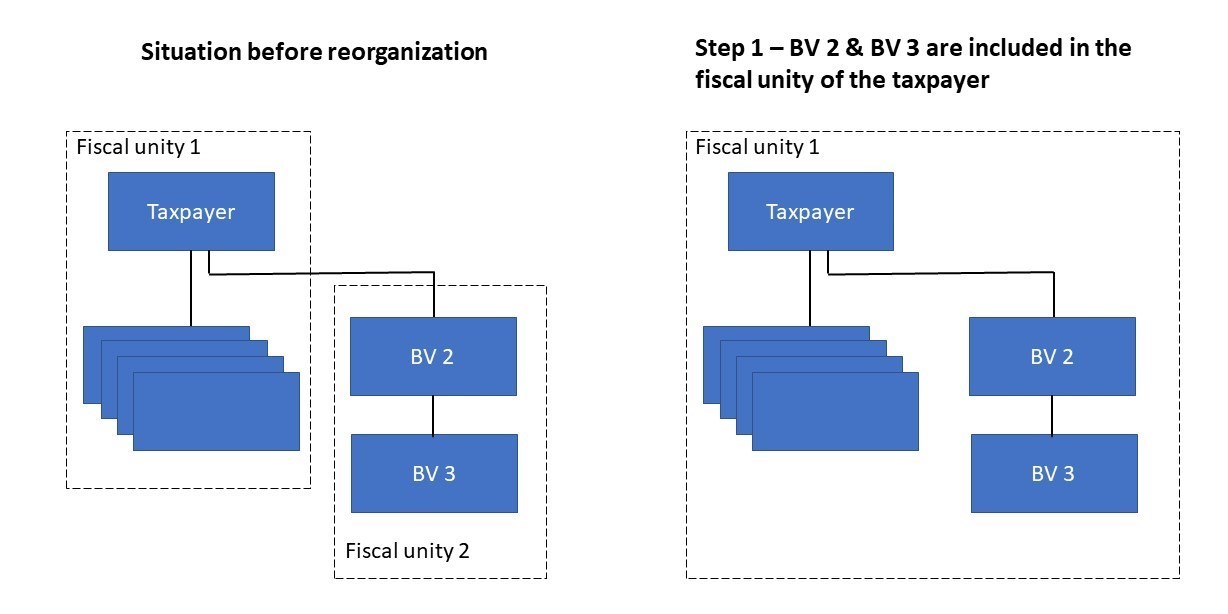

· The taxpayer has obtained several entities. These entities were at the time included in a fiscal unity that was led by BV 2;

· Subsequently the taxpayer formed a fiscal unity with several entities it had obtained under the previous step. The taxpayer was the parent company of this fiscal unity;

· In the years to follow the fiscal unity of which the taxpayer was the parent entity incurred losses. Whereas the fiscal unity of which BV 2 was the parent company (and BV 3 was (one of) the other members) realized taxable profits;

· The taxable loss that the fiscal unity of the taxpayer incurred in 2010 amounted to EUR 2,102,550.

Restructuring

The group restructuring took place according to the following steps:

1. The fiscal unity of the taxpayer is expanded with the fiscal unity of BV 2 and BV 3;

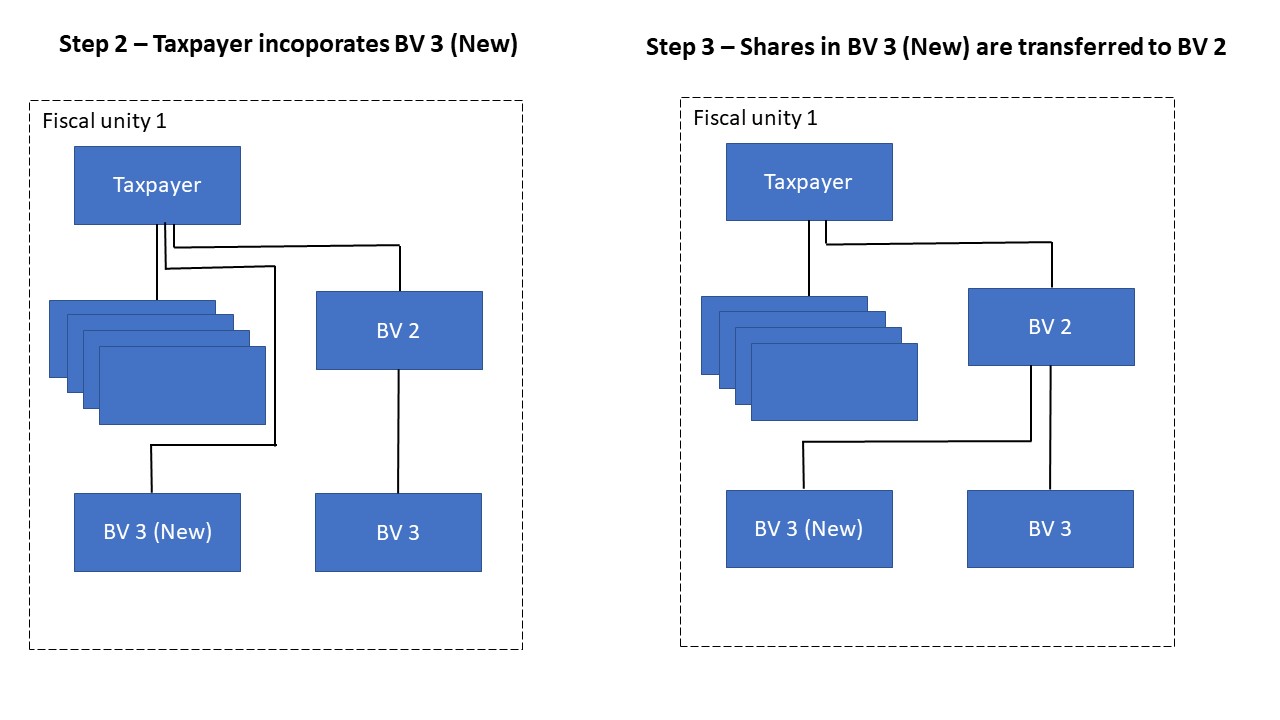

2. The taxpayer incorporates BV 3 New. As per the date of its incorporation BV 3 New is a member of the fiscal unity of the taxpayer;

3. The shares in BV 3 New are transferred form the taxpayer to BV 2;

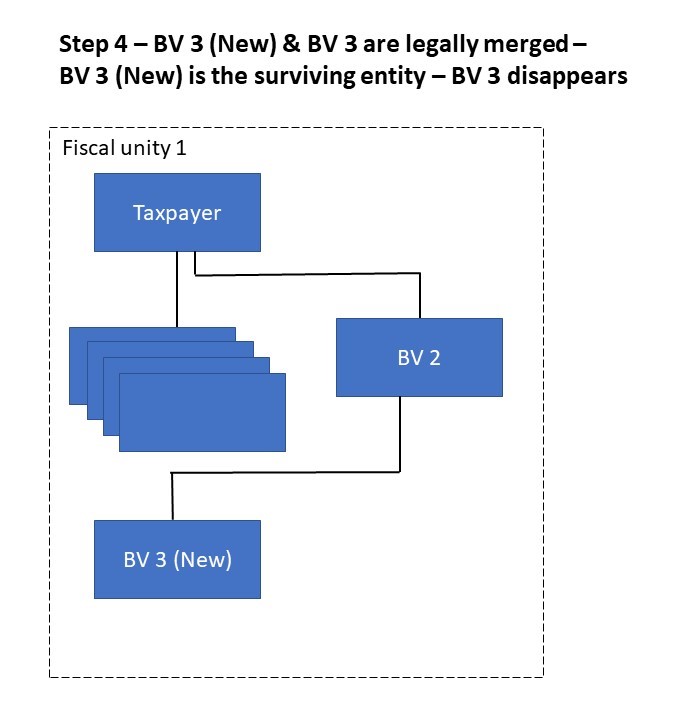

4. A legal merger takes place within the fiscal unity. In this merger, BV 3 New is the acquiring entity and BV 3 (Old) is the disappearing entity. In addition, in accordance with Article 18, paragraph 8, of the Fiscal Unity Decree 2003 (BFE) (Text of 2015) a request was filed to not break-up/end the fiscal unity with respect to BV 3 (Old) (Article 18, paragraph 1 of the BFE).

On December 6, 2016, the taxpayer filed a 2015 DCIT return for the ‘new’ fiscal unity. In this 2015 DCIT return the taxpayer reported a taxable profit of EUR 614,426 for the ‘new’ fiscal unity. This profit is entirely attributable to the business of BV 3 New and fully relates to business that BV 3 New acquired from BV 3 (Old) through the legal merger (Step 4 described above). In the tax return the taxpayer request to set off the 2010 loss against this 2015 profit (NB this 2010 loss was incurred before BV 3 Old and BV 3 New were part of the fiscal unity). Consequently, no DCIT would be due over 2015.

On November 16, 2017, the taxpayer filed a 2016 DCIT return for the ‘new fiscal unity. In this 2016 DCIT return the taxpayer reported a taxable profit of EUR 625,476 for the ‘new’ fiscal unity. In the tax return the taxpayer request to set off the 2010 loss against this 2016 profit. Consequently, no DCIT would be due over 2016.

In the assessment the tax inspector issued, the tax inspector denied the setting off of the 2010 loss with the taxable profits from 2015 and 2016.

The dispute

The taxpayer and the tax inspector are disputing whether or not the 2015 and 2016 taxable profits allocable the business of BV 3 New can be used for setting off the 2010 loss of the fiscal unity. Furthermore, the taxpayer and tax inspector are disputing whether or not the fraus legis doctrine applies in the underlying case. Lastly the taxpayer and the tax inspector are disputing whether or not a taxpayer/BV 3 New is obliged to amortize goodwill that it has included on its balance sheet.

From the analysis of the Court

Application of legal provisions

The main rules regarding the settlement of losses within a fiscal unity are laid down in Article 15ae of the DCIT Act. Based on Article 15ae, paragraph 1, sub a, losses incurred by an entity before this entity is included in a fiscal unity (pre-consolidation losses) can be set off against the taxable profits realized by the fiscal unity, insofar as this profit is attributable to that entity itself. (AJT: NB please note that the District Court of Gelderland refers to article 15ae, paragraph 1, sub a, whereas I feel that based on how I understand the facts it is article 15ae, paragraph 1, sub c that applies to the facts of this. However, I do not feel that this would lead to another outcome).

Pursuant to Article 5, paragraph 4, of the BFE, for the purposes of Article 15ae, paragraph 1, of the DCIT Act, the profit that is attributable to a subsidiary that has been part of the fiscal unity from its date of incorporation is regarded to be the profit of the companies that have incorporated this subsidiary in proportion to their capital contributions at incorporation.

On [date] BV 3 New was incorporated by the taxpayer. And from the date of its incorporation BV 3 New has been part of the taxpayer’s fiscal unity. Pursuant to Article 5(4) of the BFE, the profit of BV 3 New is therefore to be regarded as profit of the taxpayer.

Subsequently, a legal merger took place within the fiscal unity. In that context, Article 18 of the BFE contains regulations. The taxpayer has submitted a request as referred to in the first paragraph of that article. Article 18, paragraph 1 of the BFE reads as follows:

“If, in the event of a merger as referred to in Article 14b, paragraph 1, of the DCIT Act, a subsidiary belonging to a fiscal unity ceases to exist, the acquiring legal entity is part of the same fiscal unity and all that has been acquired through the merger will become part of the capital of said fiscal unity, at the request of the parent company of the fiscal unity, the fiscal unity will be deemed not to have been broken-up/ceased to exist with respect to the disappearing subsidiary and as of the date of the merger the special arrangements set out below will apply.”

Article 18, paragraph 2 of the BFE reads as follows:

“The settlement of pre-consolidation losses of the disappearing subsidiary as referred to in Article 15ae of the DCIT Act against the taxable profit of the fiscal unity, and the settlement of a loss of the fiscal unity with the taxable profit which that subsidiary realized before the merger, takes place as if no merger has taken place.”

The Court is of the opinion that, contrary to the tax inspector’s opinion, Article 18 paragraph 2 of the BFE does not apply in the underlying case. Reason here for is that it has not been shown that BV 3 (Old), as the disappearing subsidiary, has pre-consolidation losses available for loss carry forward.

To prevent that hidden reserves of BV 3 (Old) influence the loss settlement of the taxpayer, the profit of BV 3 New has to be determined with due observance of Article 15ah of the DCIT Act. Pursuant to the first paragraph of that article, the profit of a company is determined as if it were not part of the fiscal unity (independent profit determination). The second paragraph contains different profit-splitting rules regarding assets that were acquired within a fiscal unity, such as through a legal merger.

Pursuant to Article 15ah, paragraph 2, sub a, of the DCIT Act, BV 3 New has to determine the depreciation/amortization basis of the assets it acquired on the basis of the fair market value. Therefore BV 3 New must capitalize the goodwill that was present in the acquired business (of BV 3 (Old)).

In view of the foregoing, the Court is of the opinion that, based on the legal provisions, the taxpayer is in principle entitled to set off its tax loss from 2010 against the taxable profits that BV 3 New realized in 2015 and 2016. In doing so, the Court considers that the taxpayer has complied with the requirements as formulated in the various provisions referred to. The Court therefore rejects the tax inspector’s argument that a grammatical interpretation and application of the current articles would lead to incongruities with the intention of the legislator, and that therefore a grammatical application of the various articles should be omitted. Each of the legal provisions has its own background and rationale. The fact that when applying a grammatical interpretation, the outcome of the application of the combination of those provisions is at odds with the object and intent of one or more of those provisions if they are considered in isolation, as argued by the tax inspector, cannot justify that a different interpretation is given to this set of provisions. The provisions are formulated unconditionally and in such detail that the taxpayer can rightly invoke a grammatical interpretation of the articles, also in the context of legal certainty.

Fraus legis

In view of the fact that the taxpayer has in principle rightly invoked the provisions discussed above, the Court will subsequently assess whether there is fraus legis doctrine applies.

When acting in fraus legis, one acts contrary to the purpose and purport of the law (standard requirement) with the overriding motive being tax avoidance (motive requirement). The burden of proof to demonstrate that both requirements have been met is on the tax inspector. Before answering the question whether this is a case of fraus legis, it must first be assessed whether in general there is room for the application of the fraus legis doctrine in cases such as the underlying one.

The Court considers that various provisions of the fiscal unity regime apply in the context of the restructuring as carried out by the taxpayer. This regime is extensive and contains many provisions that have been formulated in detail and elaborately, many of which are intended to combat specific forms of tax abuse. This includes a significant number of provisions that describe when certain forms of loss settlement are not allowed. If within such a system of anti-abuse legislation there would be room for the application of the general doctrine of fraus legis, this would, in the opinion of the Court, entail an unauthorized infringement of, inter alia, the principle of legal certainty. In that context, the Court also considers that the legislator was aware of the consequences of the very complex and detailed regulations, which it created with the goal to prevent abuse. In particular, the Court notes that in the BFE it was opted to have a different system of loss settlement options to apply in case of a legal merger. This indicates that it was a conscious choice of the legislator to not regulate the situation at hand, but to leave it to the system of the DCIT Act. Finally, the Court considers that in cases such as the one at hand there is no combination of acts in which losses can be set off arbitrarily and if desired repeatedly for significant amounts and in which the levy of the corporate income tax could thus be wholly or partially frustrated by repeating a complex set of acts.

In view of the foregoing, the District Court is of the opinion that in the situation at hand there is no room for applying the fraus legis doctrine and therefore the question whether the taxpayer acted in fraudem legis no longer needs to be assessed. The tax inspector's appeal on the fraus legis doctrine fails.

Goodwill amortization

Regarding the question whether goodwill must be amortized on an obligatory basis, the Court is of the opinion that the tax inspector has incorrectly interpreted the law. It is in accordance with the principles of sound business practices to refrain from amortization of goodwill if the fair market value of the business has not fallen below the purchase price. According to the Court, the judgment from 1952, which was mentioned by the taxpayer, is still valid and has not, as the tax inspector argues, been set aside by new legislation in the form of Article 15ah, paragraph 2, of the DCIT Act. It can therefore be concluded that now that BV 3 New is not obliged to amortize the goodwill it acquired from BV 3 (Old), BV 3 New has determined its taxable income in accordance with the principles of sound business practices.

Judgment

The Court rules in favor of the taxpayer and grants the taxpayer the right to set off the 2010 pre-consolidation loss against the 2015 and 2016 taxable profits. Furthermore, the District Court ruled that the BV 3 New is not obliged to amortize the goodwill it acquired from BV 3 (Old).

Some final remarks

As stated above if the Gerechtshof Gelderland (the Higher Court of Gelderland) and ultimately de Hoge Raad der Nederlanden (the Dutch Supreme Court) confirm the judgment of the District Court of Gelderland then it seems that the taxpayer in the underlying case has found a backdoor to access pre-consolidation losses of a fiscal unity and therewith avoiding expiration of unused tax losses.

In principle the taxable profits of an entity that is later added to a fiscal unity cannot be used to set off pre-consolidation losses of the fiscal unity of which the aforementioned entity becomes a member. However, because of a carefully carried out restructuring, which includes a legal merger and filing the right requests in a timely manner, the District Court of Gelderland allowed the taxpayer to set off the pre-consolidation losses against the taxable profits allocable to the business of an entity that was later included in the fiscal unity and that after its inclusion in the fiscal unity was legally merged into a newly incorporated entity.

So which are the steps that seem to be critical for such a restructuring being successful:

· The entity of which one wants to use the profits has to be included in the fiscal unity;

· A new entity has to be incorporated by one or more of the entities that were part of the old fiscal unity. In the underlying case the new entity was incorporated by the parent entity of the existing fiscal unity;

· A legal merger has to take place within the fiscal unity. The newly incorporated entity has to be the acquiring entity and the profitable entity is the disappearing entity; and

· In accordance with Article 18, paragraph 9, of the Fiscal Unity BFE a request is filed to not break-up/end the fiscal unity with respect to the entity that ceases to exist when the legal merger takes place (Article 18, paragraph 1 of the BFE).

Since in my view also under current law it is still possible to use the restructuring as undertaken by the taxpayer in the underlying case to get access to the settlement of pre-consolidation losses of an existing fiscal unity, it will be interesting to follow this case and to see whether the tax inspector will go appeal against the District Court’s judgment.

Can a similar restructuring save tax losses of a stand-alone entity in danger of expiring unused

It is also an interesting question whether the judgment in the underlying case also opens the door to a restructuring and a legal merger via which a fiscal unity can be used to get access to pre-consolidation losses of a stand-alone entity. For example by having the stand-alone entity acquire another profitable stand-alone Dutch entity. Form a fiscal unity with this newly acquired entity. Subsequently have the parent entity of the fiscal unity incorporate a new entity, which from its date of incorporation will be part of the fiscal unity. And then within the fiscal unity have the old profitable stand-alone entity legally merge in the newly incorporated entity and file a request as meant in Article 18, paragraph 9 of the BFE.

If the Dutch Supreme Court comes to the conclusion that in the underlying case the taxpayer indeed has access to the pre-consolidation losses of the fiscal unity. And if the legislator doesn’t draft new legislation, I feel that there is a reasonable chance that the restructuring as described in the paragraph above and if carefully carried out can be used to avoid the tax losses of a stand-alone entity to expire unused. Most important features for success would be:

· Including an existing profitable entity in the fiscal unity;

· Correct funding of the acquisition of the profitable entity;

· A newly to be incorporated entity;

· Which is incorporated by the entity that incurred the pre-consolidation losses;

· A legal merger within the fiscal unity;

· The newly to be incorporated entity is the acquiring entity;

· The profitable entity that was later added to the fiscal unity is the disappearing entity;

· The filing of a request as meant in Article 18, paragraph 9 of the BFE.

Copyright – internationaltaxplaza.info

Follow International Tax Plaza on Twitter (@IntTaxPlaza)